English Embroidery from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ca. 1580–1700: ’Twixt Art and Nature was the third exhibition resulting from a collaboration between Bard Graduate Center and The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The exhibition, a key component in the BGC’s History and Theory of Museums concentration, drew from the Met’s preeminent collection of embroidered objects made for secular use during the late Tudor and Stuart eras. These objects have usually been regarded as a discrete body of work, removed from any sense of their original settings and contexts. However, the embroideries were created and used by the gentry of England for personal adornment and to decorate their homes, and feature designs and patterns that reflect contemporary religious ideals, education concepts, and fashionable motifs. One of the principal goals of this exhibition was to give aesthetic and scholarly credence to these often technically complex, thematically rich, and compelling objects. The significance of the objects within the social and cultural economy of 17th-century domestic life was examined by juxtaposing them with contemporary prints, books, and decorative arts.

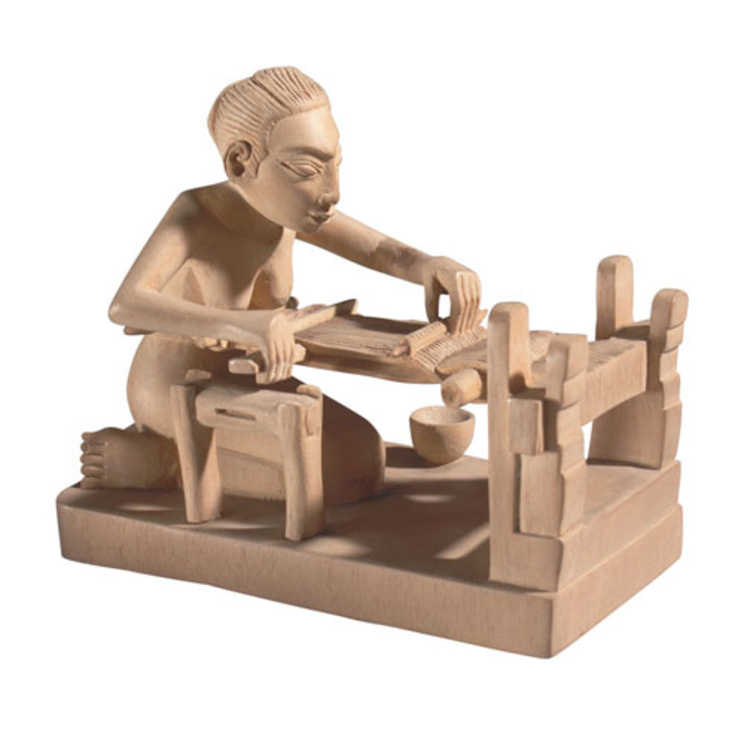

English Embroidery was composed of approximately 80 objects from the Met’s collection of embroideries and comparative supplemental material from the museum and other institutions and private collectors. The exhibition was presented on three floors of Bard Graduate Center and was organized in sections that explored thematic and typological characteristics of the embroideries. Original printed images and texts, combined with high-quality photo reproductions, helped viewers contextualize the embroideries in a way that had not been attempted previously. There was also a special animation component, consisting of two digital videos that demonstrated stitch techniques, to enhance visitors’ understanding of this art form.

The exhibition aimed, therefore, to further historical understanding of the material by combining historical interpretation with the best in museum practice. The technical sections used macro and x-ray photography to demonstrate the complexity of embroidery techniques and the variety of constituent materials in a manner never before realized in exhibition form. The adjoining displays of the stages of girlhood education demonstrated concretely the historical process by which these techniques were learned and developed. At the same time, each section illustrated the specific social and cultural meanings of the forms and subject matter, and showed how the themes employed in needlework reflected values of domestic harmony and new ideals of social grace and gentility.

The introductory section on the first floor was centered on the theme of royalty and served to provide historical background for the visitor. It contained objects of courtly ceremonial and domestic pieces that reinforced the importance of the idea of monarchy to court and country throughout a period in which stable rule under the Tudors was followed by civil war, regicide, and the eventual restoration of monarchy under the Stuarts. Among the ceremonial objects in this section were a spectacular burse (purse) made to hold the Great Seal of England and a lavishly embroidered Bible associated with Archbishop Laud. A number of embroidered portraits were displayed, including a unique Elizabethan portrait of a woman, possibly Queen Elizabeth herself, and a finely worked “portrait miniature” of Charles I, based on engravings by Wenceslaus Hollar. This latter work testifies to the deeply intimate nature of the cult of the Martyr King that arose after Charles’s execution. Another featured object was a beaded and embroidered basket with representations of Charles II and Catherine of Braganza, made in celebration of the royal marriage and restored monarchy.

The overarching theme of the second-floor galleries was the use of embroidered objects within the domestic setting. There were three specific motifs: the role of embroidery in the education of girls and young women, the survival of rare and precious accessories of dress, and the production and function of domestic furnishings. On display were several samplers representative of the types created in the mid-17th century, including a rare dated workbag created and initialed by a 10-year-old in 1669, as well as exemplary literature advocating needlework skills for the well-bred young woman and pattern books from which designs were taken. A display of techniques and materials complemented the presentation of embroidery as an educational tool. Several objects, including a late 16th-century pair of gloves and a highly three-dimensional raised-work panel, were chosen to illustrate the variety and quality of materials found in 17th-century embroidery.

The display of objects related to education and technique was followed by a display of fashion accessories from the early 17th century. One rare complete garment, an embroidered jacket from about 1616, was highlighted.

Continuing the theme of objects made for domestic use, the second floor concluded with domestic furnishings produced at both the amateur and professional levels. Decorated caskets (small boxes), mirror frames, and cushions all played a role in bringing comfort and color to the home at a time when many furnishings were still transported from one home to another and most upholstery was not fixed. Two of the Met’s most spectacular caskets, as well as two equally elaborate mirrors, were shown here.

The third-floor installation explored in detail two of the most popular themes in the pictorial embroidery of the period: stories drawn from the Bible and the depiction of nature. The objects here depicted the centrality of the Bible in contemporary domestic life and reflected the use of exemplary biblical heroines as models of virtuous behavior in the upbringing of young women. Finally, a selection of embroideries was used to highlight the importance of the natural world in the decorative conventions of the time.

The accompanying publication,

English Embroidery from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1580-1700: ’Twixt Art and Nature, published and distributed by Yale University Press, was edited by cocurators Melinda Watt and Andrew Morrall and contains a complete catalogue of the objects in the exhibition as well as six essays. It is the most extensive examination of embroidery from this period ever published in the United States. In addition to the curators, contributors include Kathleen Staples, author of

British Embroidery: Curious Works from the Seventeenth Century (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1998), whose essay addresses the production and usage of embroidered furnishings; Susan North, curator of 17th- and 18th-century dress at the Victoria and Albert Museum, who has written an essay on fashion accessories; Ruth Geuter, a leading expert on pictorial embroideries, who offers an essay on the social dimensions of the embroidered biblical narratives; and Cristina Balloffet Carr, associate conservator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, who presents an illustrated technical dictionary of materials unique to these objects.

The project was cocurated by Melinda Watt, assistant curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the Metropolitan Museum, and Andrew Morrall, professor at the Bard Graduate Center, and was overseen by Deborah L. Krohn, associate professor and coordinator for History and Theory of Museums, and Nina Stritzler-Levine, director of exhibitions, both at Bard Graduate Center.

The Art of Embroidery video by Han Vu

.jpg,732x732,c)