“REvisions” is the ongoing series launched with the Research Forum in which faculty and invited contributors are invited to rummage through Bard Graduate Center’s archive of video lectures, published chapters, and print articles and discover new themes and hitherto unexplored connections. The premise is that while all these varied research “outputs” are published with a coherence evident to their conveners and editors in the moment of organization that further connections may become apparent in time. Moreover, institutional intellectual commitments mean that continuities of this sort cannot be dismissed as merely adventitious. “REvisions” therefore offers, also, an opportunity to see the “hive mind” in action: an institution as a thinking, living, collective organism.

REvisions 1: Decorative and the Antique

The historiography of the decorative arts could not emerge before there was a field of study called “decorative arts” and this, in turn, could not have emerged before the existence of institutions either devoted to it (the museum) or able to single it out taxonomically (the university). This happened first, though very imperfectly, in the latter case. The birth of academic art history in the middle of the nineteenth century could have led to an intense taxonomic focus and clarification but it did not since the new art history professoriate paid attention to paintings, sculpture and architecture, to the exclusion of almost all else (works on paper would be an exception). The decorative as a category is itself almost a pejorative back formation; the beautiful, the high-minded, the idea—all that belonged to the heightened reality of the framed illusion. Aside from being worldly, the decorative could all too easily become the “merely” decorative in a way that no Titian or Rembrandt ever could. The birth of museums devoted to “Applied Art” came at the middle of the nineteenth century, most notably in South Kensington, and those devoted to “Decorative Art” (Kunstgewerbe) came later in the century. Applying the label of “applied” did not help the status of those objects since it reified the subordination already implicit in a hierarchy that privileged the “Idea” over all else. Moreover, applied learning always had more than a whiff of the vocational about it—it still does, in fact—and that made it a poor child in a world still swearing by art for art’s sake.

Moreover, these very years were those in which anthropology emerged as a defined academic discipline. Its turn to study how people lived outside of Europe opened up the study of whole categories of life such as clothing, tools, food, narcotics, dwelling and decoration. The word applied to this package was “culture.” The force of this new field of study is registered in Jacob Burckhardt’s choice of the word “culture” to describe the Italian Renaissance in his classic study of 1860: Der Kultur der Renaissance in Italien. That this same approach was hard for Victorians the world over to stomach is reflected in the fact that the work’s English translator replaced “Kultur” with “Civilization”—and so, 157 years later, we talk about The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. The value accorded the decorative could well be said to rise and fall in sync with that of “culture.”

Bard Graduate Center was founded at exactly the time, in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of Communism, when culture began its meteoric rise as the leading explanans in the humanities. And so, even as the institution took the term for its title (“Bard Graduate Center for Study of the Decorative Arts”) it proclaimed in its first course catalogue that the scope of the decorative was global and trans-historical. The kernel of the idea was there at the start and over the successive years it sprouted as the institution advanced into ever-broader chronological and geographical periods.

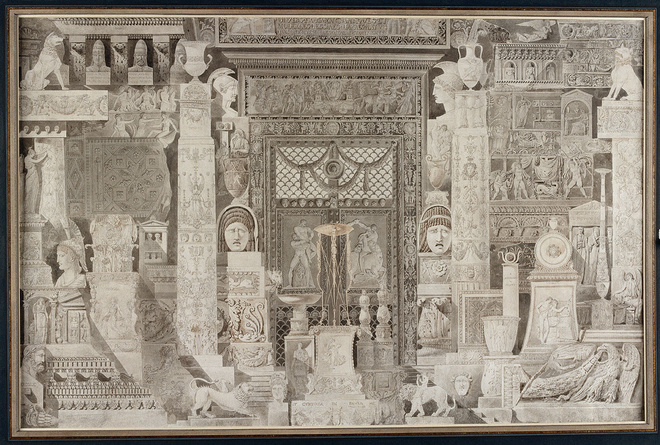

But as with Burckhardt himself, Bard Graduate Center’s idea of culture remained tied to the study of antiquities. (It was Arnaldo Momigliano who wrote that if the Renaissance could be described as the “revival of antiquity” then it could be even better, that is, more accurately, described as the revival of the study of antiquity.) From the very first exhibition On the Royal Road, up to the most recent, Charles Percier, the connection between antiquity and the decorative has been a constant presence in Bard Graduate Center research. Sometimes, it has been explicit, as in “A Passion for Antique Gems,” or “Kent and Italy,” and sometimes visible only to those who already knew where to look, as in “Veduta Painting at the Royal Porcelain Factory Berlin (KPM) after 1786,” or “The Metamorphosis of the Neoclassical Vase.” Behind this lay a further point of contact: the antiquary and the antiquarian. “E.W. Godwin as an Antiquary,” “Stuart as Antiquary and Archaeologist in Italy and Greece,” “The Past as a Foreign Country: Thomas Hope’s Collection of Antiquities”—in all these the later historiography of decorative arts are anchored in the earlier figure of the antiquary.

Long a forgotten figure, where not outwardly mocked, the return of interest in the antiquary among contemporary cultural historians and historians of art and scholarship is linked to the general appeal of material histories and studies, but also to the wide-ranging nature of early modern antiquarian scholarship. Polydisciplinary before there were hard and fast disciplines, antiquaries tried to understand objects and pursued their sources wherever they led. Vases, to choose but one example, survived in vast numbers from the ancient world, and they opened up many doors: on to funeral practices, weights and measures, ritual, food, preservation, trade and aesthetics. Scholars like Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1637) and Anne-Marie Turnèbe the Comte de Caylus (1692-1765) collected, studied and depicted them —but so did William Hamilton, William Beckford and Thomas Hope.

The connection between these two groups of collectors is captured in the word “Neo-classicism.” The extent to which this should be considered as a phenomenon of antiquarianism follows from our definition of the antiquarian. If he—always a he—is someone who studies the past for the sake of studying the past, viewing the past as that famous foreign country then he becomes for us almost as distant as those artifacts. But if we follow the view that the antiquarian is someone who studies the past that lives on into the present—and artifacts found, collected and studied now are alive in our present—then the antiquary becomes a bridge between past and present. The neo-classical, in turn, becomes not just the Hegelian “overcoming” or “negation” of a specifically eighteenth-century “quarrel of the ancients and moderns” but becomes the sign of all “revivals” of antiquity. For the very effort to revive is antiquarian in the specific sense of trying to put the past—some part or notion of the past—to work in the present. The antiquarian, therefore, like the neo-classical, is bound up in Bard Graduate Center’s historiographically-engaged championing of the “decorative” at the turn of the twenty-first century: still another act of revival, carried on this time as an institutional project.