“REvisions” is the ongoing series launched with the Research Forum in which faculty and invited contributors are invited to rummage through Bard Graduate Center’s archive of video lectures, published chapters, and print articles and discover new themes and hitherto unexplored connections. The premise is that while all these varied research “outputs” are published with a coherence evident to their conveners and editors in the moment of organization that further connections may become apparent in time. Moreover, institutional intellectual commitments mean that continuities of this sort cannot be dismissed as merely adventitious. “REvisions” therefore offers, also, an opportunity to see the “hive mind” in action: an institution as a thinking, living, collective organism.

REvisions 3: Counter-histories

The late Amos Funkenstein offered the notion of “counter-history” as an alternative and even mirror-image narrative whose epistemological value lies precisely in its ability to regroup material whose coherence was hitherto invisible to the eye. We might see this operating on the grand scale the way Walter Benjamin’s injunction to brush history against the grain was aimed at the reading of individual sources.

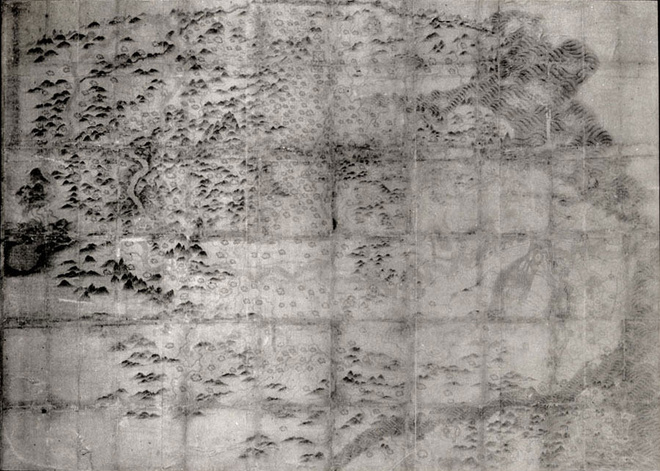

We argued in the preface to REvisions 1: Decorative and the Antique that every act of revival is fundamentally antiquarian in that bringing back the past affirms its existence in the present and “the past as it lives on in the present” is one of the compelling definitions of the antiquarian. But the historiographical recovery of the “revival” could be said to constitute a “counter-history” in just Funkenstein’s sense. Flipping the narrative lets us see the world in a different way. It is a fundamentally critical act of historiography. On this definition, we can see that Bard Graduate Center’s exhibition and publishing program has been engaged in a giant act of counter-historical exposition.

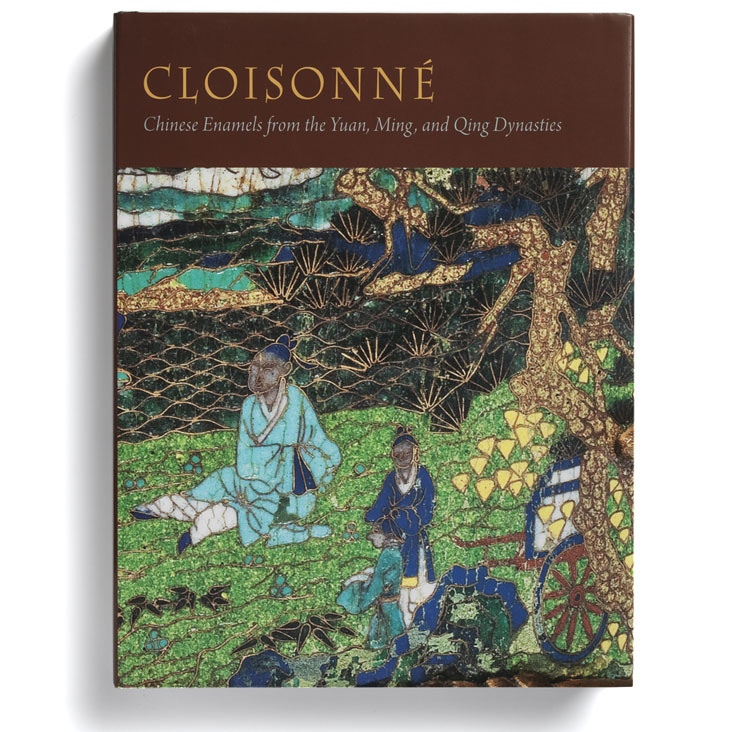

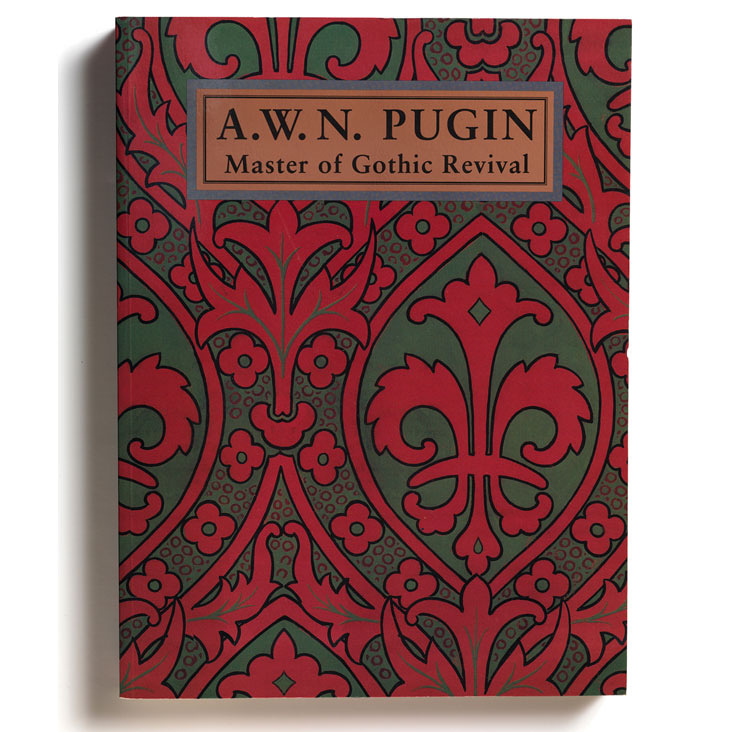

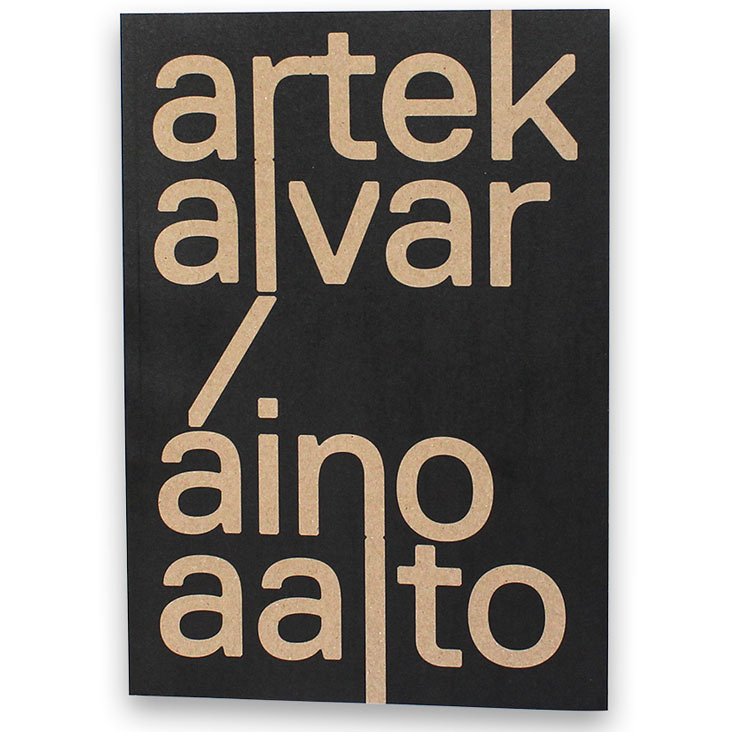

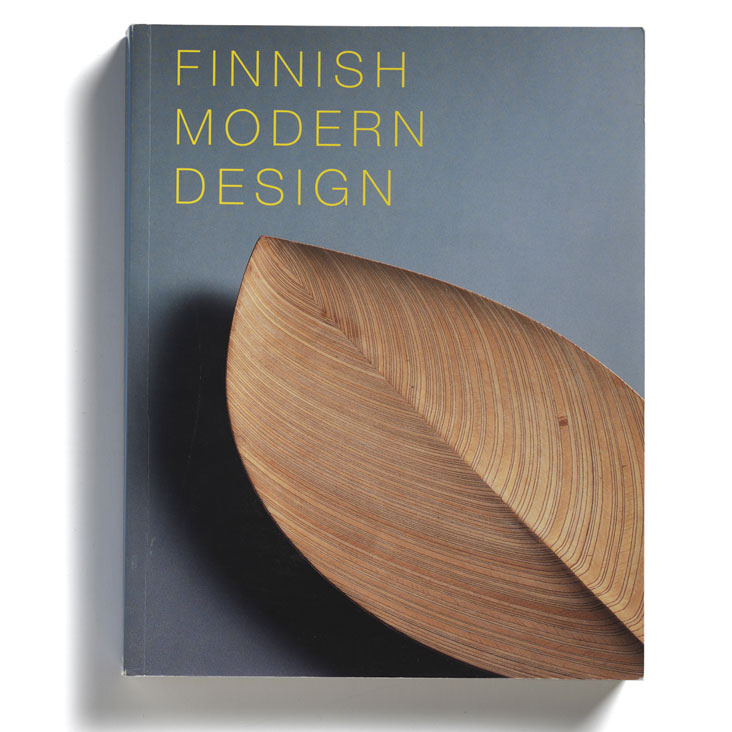

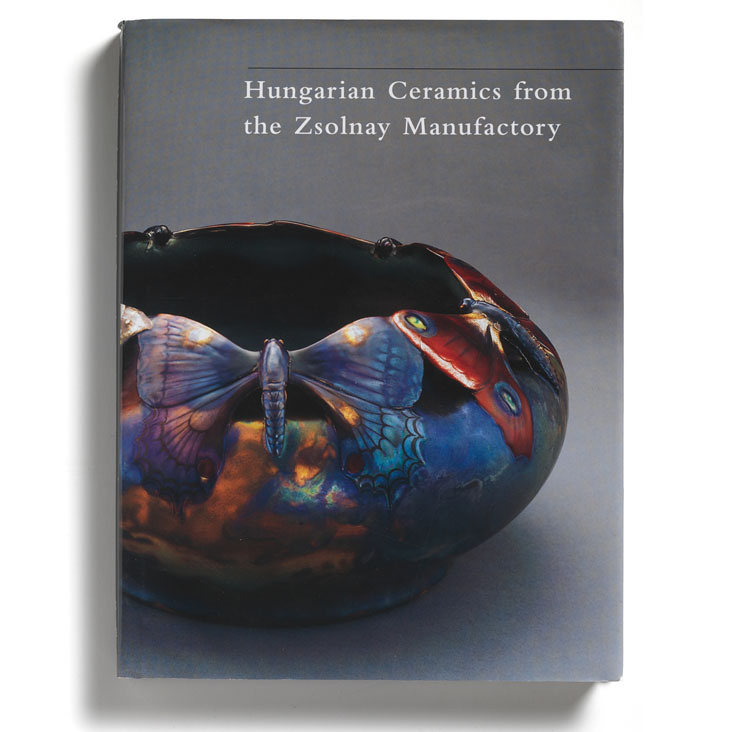

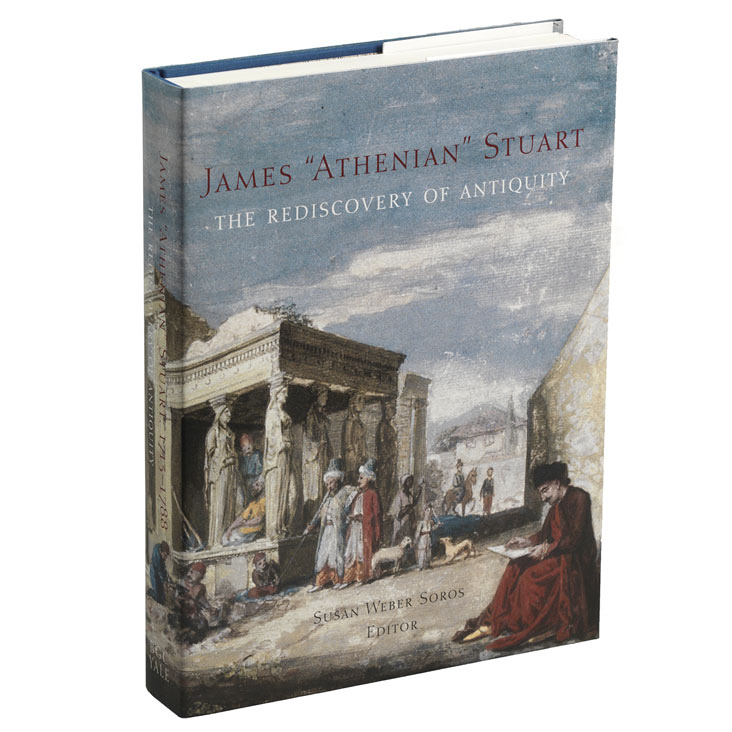

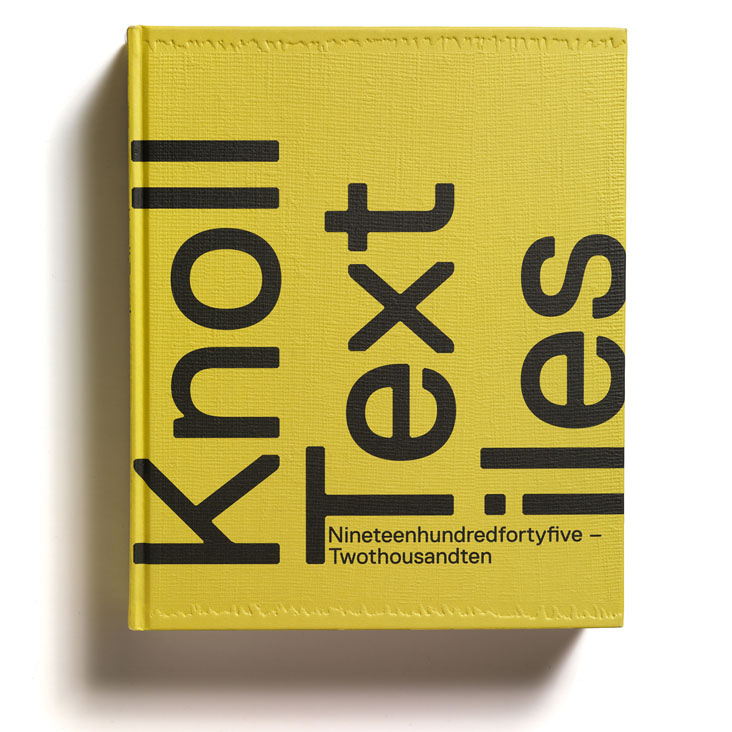

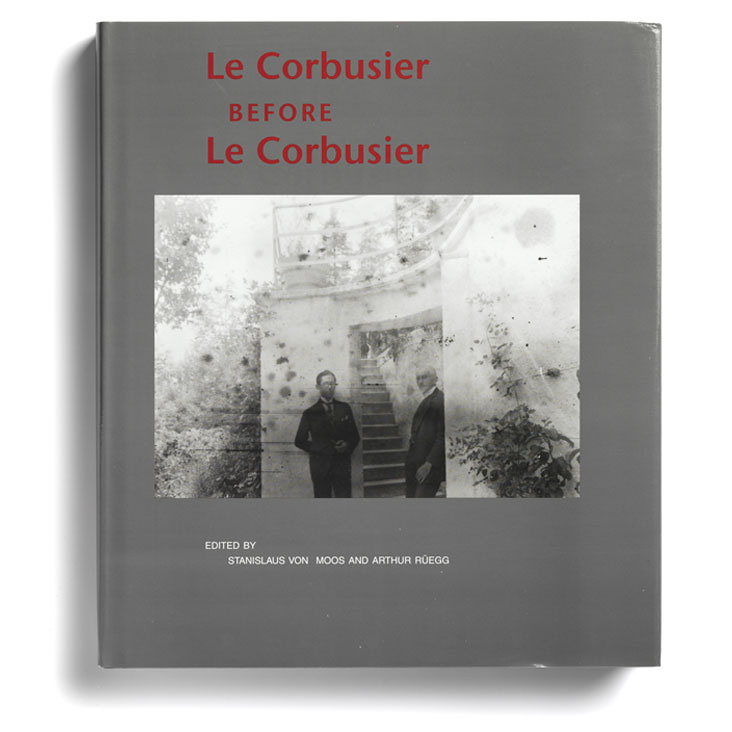

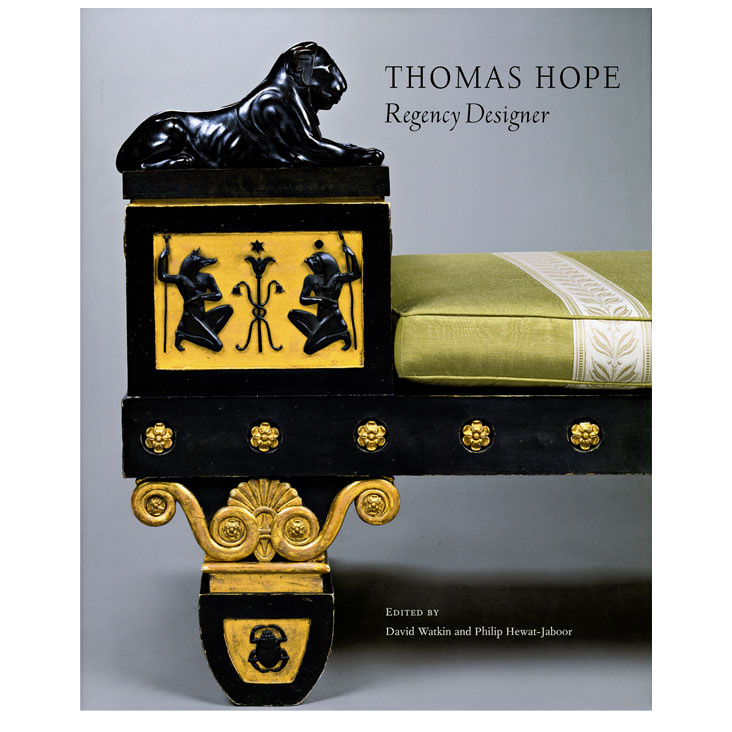

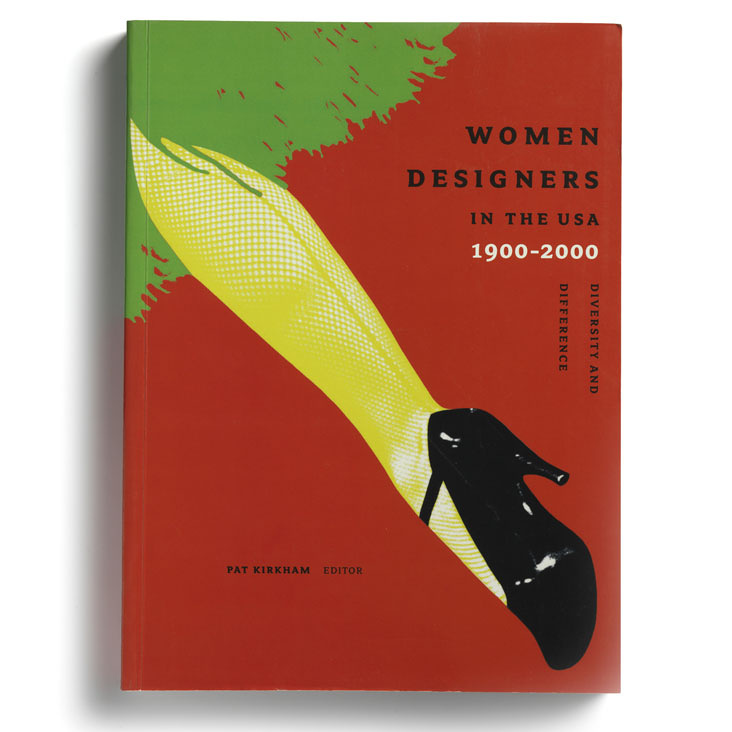

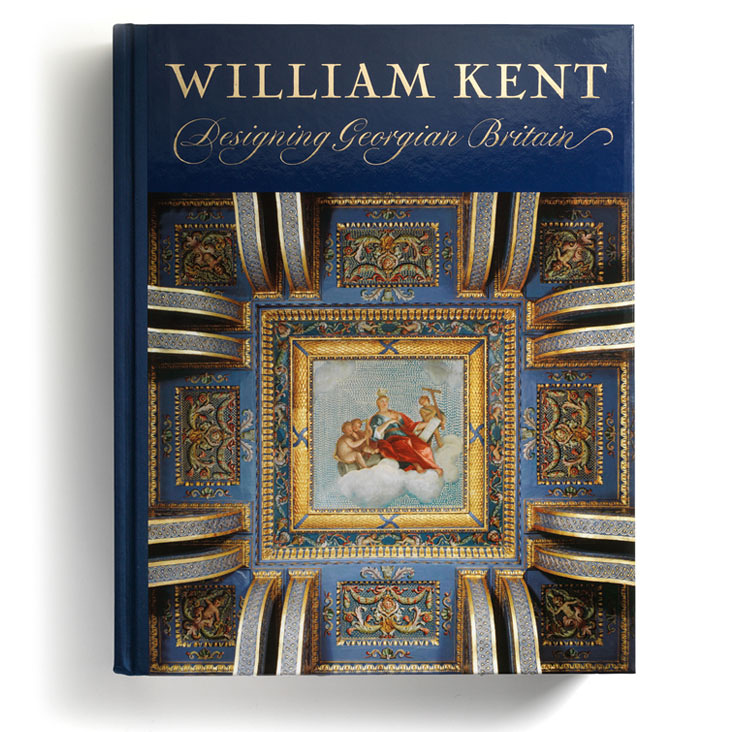

For a major strand of institutional research has been devoted to what we might describe as “alternate paths to the present.” Antiquarianism, Gothic revival, Nordic modernism, Biedermeier, late neo-classical English design, Dutch empire, votive objects—these steer clear of the Bauhaus or the Wiener Werkstatte or Macintosh or art nouveau or any of the other time- and space-warping dominant narratives of art history’s modernity Sending readers and authors and visitors back to abandoned or just dimly-known corners of the past could seem antiquarian in the worst way (the past for the past’s sake). But after twenty-five years of work these pin-pointed research projects begin to aggregate and the individual spotlights begin to illuminate larger and larger swaths of learning’s night sky. BGC’s work, looked at this way, is a collective effort to put other plots on the table, to bring to the attention of visitors and readers the fact that there are other paths and that some of them are very interesting. There is contingency in history and unless we’re all Hegelians that one or another narrative becomes canonical does not necessarily say anything about the quality or importance of the thing or movement so much as the conditions in which it was received.

REvisions 3 could be read as a map: charting contours, indicating relief (some higher than others), highlighting movement. In fact, the entire REvisions project adds up to that map, both those done and those to come. But if that’s the case, then REvisions 3 is really the meta-map, a mapping of the way in which counter-histories map. In that case it is appropriate for it to appear early on in this project since it will serve as a “legend” to the maps that follow and the larger map to which they all contribute—the BGC’s intervention in the historiography of its related disciplines.