From the Exhibition:

The Codex and Crafts of Late Antiquity

What does footwear have to do with Coptic book design?

As it turns out, a lot more than you might think. When I first began working as

Georgios Boudalis’s research assistant for the exhibition The Codex and Crafts in Late Antiquity, I did not expect to be

combing through museum databases in search of hand-woven socks and finely

stitched shoes, yet some of my biggest research breakthroughs came while

analyzing the sewing structure and the gilding pattern seen on antique Coptic

shoes.

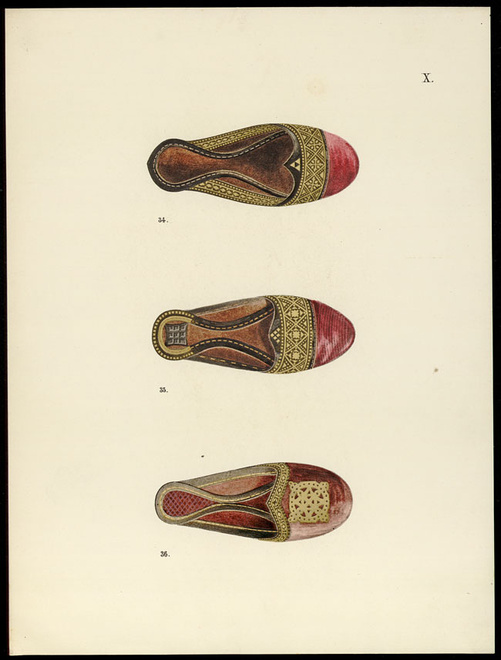

The backless shoe, or mule, seen above, one of a pair

in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Islamic collection (fig. 1), originated in Panopolis,

Egypt, in the 4th–7th century AD. The

mule’s sumptuous leather may have been a deeper red color at the time it was

made. In any case, it is this red tone that gave our modern-day mule shoes

their name. Mulleus calceus, the

shoes commonly worn by aristocratic Romans, were a color similar to that of red

mullet fish (mullus); scholars

believe that the term mulleus was

shortened over time to produce the word we use today—mules. Many

such shoes were preserved in the desert gravesites of Panapolis, near the

modern Arab city of Akhmim (fig. 2).

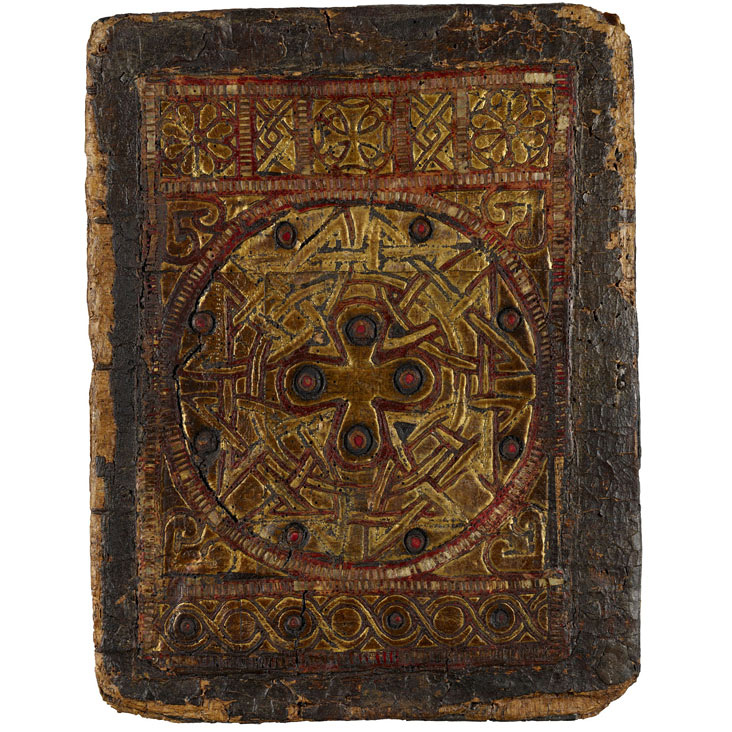

The shoes and the covers from bound Coptic manuscripts

featured in the exhibition were fabricated out of similar leathers, but their

connection runs deeper than the color of the leather. The gilded decoration

adorning both the shoe and the manuscript covers and the process of its

application also draw the pieces together. In both examples, gold foil was

adhered to the leather to create a dazzling ornamental pattern.

Although decorative ornament may seem, at first glance,

to serve the sole function of beautifying an object, decoration found on

leatherwork also constitutes a form of language. Embedded in the interlacing

diamonds, crosses, and squares are cultural meanings that are not readily

accessible to the modern viewer. There are different possible explanations as

to why these two disparate forms—shoes and books—possess similar designs. They

might draw from a common pool of decorative patterns reflecting the fashion,

taste, or even symbolic meanings of the era. Unfortunately, owing to scant

written records explaining the reason for commonalities between forms, we will

likely never be able to draw a definitive conclusion.

From a practical standpoint, we must first consider

the artisans who created the works in question. The process of creating

manuscripts was not as streamlined as one might assume, since the task was

assigned not to a single monk in a monastery but to numerous scribes and

manuscript illuminators who wrote and decorated the texts and created the illuminations.

It is also clear from the execution that skilled leather workers fabricated the

decorative covers. Because of technical similarities between the sewing and

gilding of both the shoes and the manuscript covers, as well as their comparable

design schemes, evidence seems to indicate that leather workers worked across

both mediums, creating both sacred and quotidian objects.

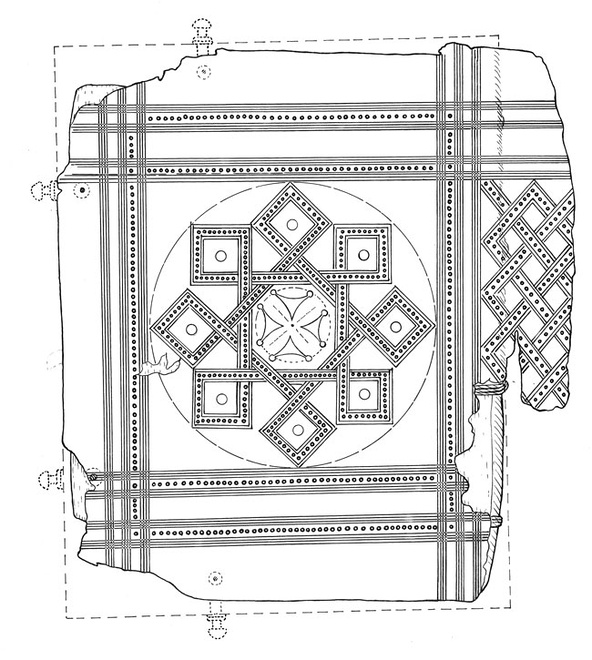

The similarities between the shoes and manuscript

covers also extend beyond their technical execution; clearly the style and

possible function of the decoration knit the two forms together. Angular

geometric designs, like those found on the shoes, also serve as a chief

decorative feature of the Morgan Library manuscript M. 574 (fig. 3). Likewise,

we find similar diamond patterns in floor mosaics situated at the entrances of

Coptic and Byzantine churches of the era.

It is difficult to explain the similarities between

the patterns on the shoes and those on the manuscript covers, as we can never

know exactly what the artisans who created them intended. Clearly some of the

patterns found on manuscripts had symbolic meanings, but did these same

meanings extend to shoes? Perhaps the artisans wanted to demonstrate their

artistic virtuosity across a variety of mediums, or perhaps they simply wished to

create a beautiful pair of shoes for a wealthy patron. These unresolvable

questions underscore the difficulties that come with studying objects that date

back over fifteen hundred years.

Darienne Turner received her MA from Bard Graduate

Center in 2017.