Originally published in: Cloisonné: Chinese Enamels from the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties, edited by Béatrice Quette. New Haven and London: Published for the Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture, New York by Yale University Press, 2011. 81-103.

Cloisonné enamels were made in a wide repertoire of forms

and with an extensive array of colorful designs. Although not all cloisonné

shapes and decorations followed ancient styles, a significant number of pieces depended

on archaism as a major element. Archaic patterns were derived from ancient

bronzes, as well as from artifacts dating to the more recent dynasties of Song

and Ming. Some concepts came

directly from catalogues of ancient bronzes

that were illustrated with monochrome line-drawn woodblock

prints. Many objects reveal a disregard for convention

and incorporated traditional elements into schemata derived from textiles, ceramics, and other

sources.

Why should archaism have had

such a significant impact on cloisonné, a medium whose techniques of

manufacture and exuberant palette of colors made it so different from genuinely

ancient artifacts? The most obvious explanations have to do with function and

patronage.

As to function, it is evident

that a large number of cloisonné vessels were made for altars in palaces,

temples, and other formal settings. Written texts, paintings, and old photographs

illustrate the pervasive use of cloisonné in religious and ritual contexts.

Furthermore, cloisonné hardly ever occurred in burial contexts, indicating that

it was not placed in tombs, as many treasured personal or household effects

were.

As to patronage, the expense and

sumptuousness of cloisonné insured that it was used chiefly in milieus calling

for a luxurious decorative effect, and so it was commissioned and owned by a

small social elite, at the top of which was the imperial court. Cloisonné

objects were made for palace halls and imperial temples. Emperors and members

of the court presided over religious and state rites at Buddhist, Daoist, and

Confucian temples, as well as at state temples, and they had under their

jurisdiction numerous palaces in the capital, summer palaces to the north, and

many other notable buildings throughout the empire.

Of course, worship was not

restricted to the imperial court. Temples served members of the religious,

military, and bureaucratic elites, as well as neighborhood communities in

villages, towns, and cities across China. Even the scholar-gentry, whose

alignment might seem to have been primarily with Confucian codes of conduct,

sponsored Buddhist temples and monasteries. Timothy Brook has described how by

the late Ming dynasty, the scholar-gentry expressed their power and patronage

through a broad range of social and economic strategies, among the most

significant of which was patronage of the Buddhist religion. Indeed, the

embodiment of Ming patrician values, the famous scholar and arbiter of values

Wen Zhenheng (1585-1645) discussed the arrangement of his personal

“Buddha chamber” in a book devoted to refined taste.

During the Yuan, Ming, and Qing

dynasties, temples were more than simply buildings in which to worship. Susan

Naquin has pointed out the lack of communal space, such as parks, promenades,

squares, fountains, gardens, or stadiums, in Chinese cities. This, coupled with

government strictures on public assembly, led to temples being the most important

element of public space, freely open to all and protected by the acknowledged

legitimacy of their religious purposes. Their

importance was thus of considerable relevance to the general populace of China,

and they provided a very public arena for displays of piety and sponsorship.

The most common gifts to temples

were of money and land. Patrons paid for the construction and maintenance of temple

buildings and the purchase of images, ritual paraphernalia, incense, and

candles. Ritual vessels and implements were commonly made in gilt cloisonné, an

ostentatious material that flaunted its cost and showed up well in dim halls

filled with incense smoke. As in many fields of study in China, a high

proportion of surviving documentation relates to gifts originating from the

imperial court. During the Ming dynasty, women of the imperial family and

palace eunuchs were the most generous donors, particularly to Buddhist temples.

For example, Madame Li (1546-1614), consort of the Longqing emperor and mother

of the Wanli emperor, was a pious and devoted patron. Her gifts in one year

(1593) included a handsome embroidered robe, a large incense burner, and the

overall gilding of a life-size statue of Shakyamuni. During the Qing dynasty,

palace eunuchs ceased to play such a significant role, and emperors took their

place as patrons, along with female devotees whose devotional activities

continued. Thus in 1764, the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736-96) presented gifts to

the Tanzhe Monastery (潭柘寺; Monastery of the Pool and the Mulberry) in the Western

Hills outside Beijing, while his mother, the Xiaosheng empress dowager, donated

cloisonné ritual implements to the abbot. Such imperial gifts were readily

supplied from the Imperial Household Workshops, which kept up a steady

manufacture of luxury items in a variety of media, including gold, silver,

gilt-bronze, and gilt-cloisonné enamel. Altar vessels were kept in stock in the

palace storerooms and assembled into sets when needed. Old, tarnished, and worn

objects could be melted down and recast into new sets, and cloisonné items were

regilded.

Ritual implements included

bowls, dishes, statues, bells, and shrines. By far the most common assemblages,

however, were the set of five vessels placed on altars. Known as the

“five-offering vessels” (wugong, 五供), the set comprised a central incense

burner with two flanking flower vases and candlesticks. Sets of five offering

vessels ornamented temple altars, palace halls, and household shrines and were

used at funerals in the Ming and Qing dynasties. It is not surprising,

therefore, that many cloisonné vessels are in the shape of incense burners and

vases. Candlesticks are less common, although they do survive.

As to pieces manufactured for

temple altars and formal palace settings, the adoption of archaic forms and

decoration followed conventions that required vessels in bronze shapes to be

used for ritual undertakings. This was strongly observed with regard to state

ceremonies, when the emperor offered religious sacrifices in his role as Son of

Heaven and Ruler of China at the Temples of Heaven, Earth, Sun, Moon, Agriculture,

the Imperial Ancestors, and the Guardian Deities of the State and Harvests.

State sacrificial ceremonies can be traced back as far as the Bronze Age, when

detailed regulations are described in such books as Zhou li (周禮; Rituals of Zhou) and Li

ji (禮記; Book of Rites). By the Song dynasty,

it was necessary for the Huizong emperor (r. 1101 -25) to reiterate the need

for ritual vessels based on ancient bronzes. At the beginning of the Ming

dynasty, by contrast, the frugal founding Hongwu emperor (r. 1368-99) decreed that

conventional bowls and plates should be employed for rituals, although names of

traditional bronze vessels—deng (燈), xing

(鈃), bian

(扁), dou (豆), fu (簠), gui (簋), jue

(爵),

and zun (鐏)—be

used to describe them. In the eighteenth century, the Qianlong emperor

showed renewed concern with correct ritual and process and wished that rites were

performed as in ancient times. In the first part of his reign in 1748, he

reinstituted the use of vessels in archaic forms to replace the conventional

bowl and plates that had been employed since the Ming. This event affected

the general fashion for implements, including those in cloisonné.

Cloisonné enamel objects were

not used solely for religious purposes, however, and many items served as

furnishings because of their decorative qualities, their ostentation, or their

grandeur. Generally speaking, these contexts provided a reason for archaism,

since one of the defining features of Chinese thought and culture is a strong preference

for antiquity. Anything that achieved the status of “ancient” was

viewed with nostalgia, and even objects conceived in an “old” style

had a connection with what was felt to be a superior time, i.e., the past. Archaism was considered

synonymous with the cultivation of refinement in craftsmanship and with a high

stylistic level thought to be missing in contemporary times.

Some Cloisonné Vessels

Derived From Ancient Bronze

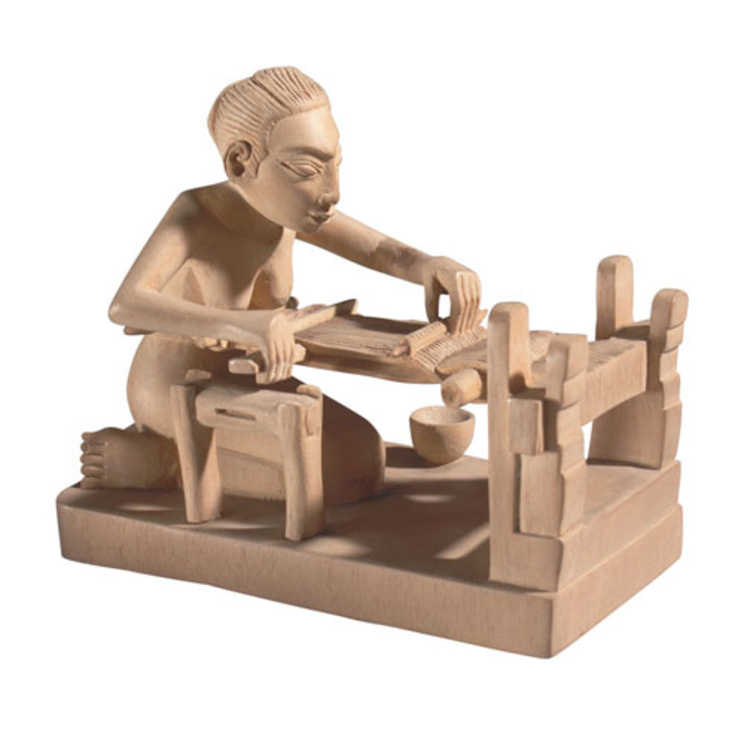

Today we identify ancient bronze vessels by a series of terms

that define their names and function—gu

(觚), jue, zun, ding (鼎),

and so on. To scholars and students, these terms serve as a shortcut to the

identification of objects of enormous complexity and variety. The descriptive

terms, however, were devised long after the periods in which the bronzes were made,

dating to the time when antiques were first classified, catalogued, and

illustrated, during the reign of the Huizong emperor, an avid collector, in the

Northern Song dynasty.

It is possible that all cloisonné

vessels that followed ancient shapes, however loosely, were influenced by

ancient bronze or jade. In some instances, however, cloisonné pieces mimicked

complicated ceremonial bronzes quite closely, a trend already evident early in

the Ming dynasty. [An example from the musée des Arts décoratifs (23.585)] illustrates

a simple form of the archaic vessel known as gui, whose style derived from vessels of the Western Zhou dynasty.

Today we have numerous excavated examples that help date the form with some precision,

and objects can even be associated with types of burial within a ranking system

of nobility. For example, a gui

vessel belonging to Earl Ju came from a tomb of the middle- or low-ranking

aristocracy. It was among an assemblage excavated near present day Beijing, an

area governed by the enfeoffed state of Yan during the Western Zhou period. At the time the object was made, in the

fifteenth century, such detailed information was unknown. However, excavated

artifacts already existed in collections and illustrated catalogues augmented

the craftsmen’s knowledge of archaic shapes.

By the

early Ming dynasty, ancient styles were combined with surface decoration that

was both refined and diverse. By way of illustration, [a vase from the musée

des Arts décoratifs (23.629)] is shaped like a ceremonial gu vessel, with bronzelike flanges and leaflike blades rising on

the neck. Its enameled scheme, however, is closer to that found on contemporary

porcelain, comprising grapevines and several carefully depicted varieties of

flowers.

There are a large number of Qing

dynasty items in this exhibition that are based on archaic bronzes. Catalogue number

75 is in the form of a pouring vessel called a yi (匜), which corresponds

to artifacts that we now date to the Spring and Autumn Period (770-475 B.C.).

It has four animal-like legs and a spout that was originally modeled in the

form of an animal head, but by the fifth century B.C. had become abstracted and

ornamental. Its handle has animal masks on top and a pendant flange below, and

the cloisonné enamels outside are summary representations of bronzelike

dragons. Inside the vessel, the decoration resolves itself into a pleasant

design of naturalistic flowers and bamboo. In the Bronze Age, yi vessels were employed to pour water

into flat bowls called pan (盤). Catalogue number 95

is in the shape of a pan, but its pattern

is not archaistic, consisting of flowers and the Eight Auspicious Symbols of

Buddhism (Bajixiang, 八 吉 祥),

which confirms its likely use in a Buddhist setting.

Catalogue number 78 was made in

the form of the ancient bronze ceremonial vessel for wine called a jue. During the Bronze Age, jue were part of ritual sets that were

used for feasting and were subsequently interred in tombs of powerful and

upper-class individuals. Jue combined

a three-legged tripod that supported a rounded cup within a utensil that could

be set over a fire and warmed. Two posts on the lip were used to lift the cup

away from the heat, and a handle on the side was provided to pour liquids out.

In the Ming and early Qing dynasties, the names of ritual bronzes were used for

ceremonial utensils employed in state ceremonies. As discussed above, however, the

vessels were made in ceramic rather than bronze, and original bronze shapes

were not utilized. Christine Lau has demonstrated that the only archaic form to

be reproduced in porcelain during the Ming was the jue. This is curious, because the jue is one of the most difficult shapes to assemble in porcelain,

or in cloisonné, since it requires the manufacture of separate elements, which

are then combined before firing or casting. The ungainly shape of the vessel

made damage to the legs, mouth, and posts likely. Nevertheless, when the

imperial porcelain kilns at Jingdezhen were excavated, the remains of porcelain

jue were discovered in both plain and

painted porcelain. The imperial factory supplied porcelain for both

domestic and ceremonial use, and these finds thus confirm the textual records.

In the eighteenth century, the Qianlong emperor’s pronounced interest in

antiquarianism and his desire to follow procedures set down during the Xia,

Shang, and Zhou dynasties caused the reintroduction of bronze vessels in

traditional shapes. Among them, the singular jue was used in state ceremonies, but it was also set before

deities in temples and on ancestral altars. The shape of catalogue number 78 is

in Shang-dynasty style, and its decoration combines hooked volutes and a panel

of blade, with bats among floral scrolls.

An object with straightforward pedigree is the duck headed vase

in catalogue number 84. Such vessels were illustrated in volume (juan) 21 of

the eighteenth-century bronze catalogue Xiqing

gujian (西清古鉴;

Mirror of Antiquities [prepared in] the Western Halls), where they were

described as being hu (壺) vases, with wild duck heads and bent

necks, dating to the Han dynasty. Such vessels in plain bronze were in fact

made during the Han dynasty. During the eighteenth-century, the shape came into

vogue and was copied in bronze, porcelain, and cloisonné. Catalogue number 84

was decorated with an overall lozenge pattern, each cell of which contained a

flower head. As was common, the eighteenth-century cloisonné décor acted as a

point of differentiation to the archaistic form.

Many eighteenth-century

archaistic pieces did not relate so closely to extant objects but relied on

printed matter as a medium of transfer. Elephants with vases on their backs, for

example, had no origins in Bronze Age China but were illustrated in catalogues

as being of ancient provenance. Xiqing

gujian included a pair of vessels described as being elephant zun dated to the Zhou dynasty. The model

was often copied in cloisonné enamel, like the elaborate object in catalogue

number 100. A second reason for the popularity of such objects was their

connection with Buddhism. Pairs of elephants with sacred objects or vases on

their backs were used as roof tiles on Buddhist temples, at least as early as

the Ming dynasty. In the Qing dynasty, pairs of elephant zun were popular objects for temple

altars and were often manufactured in heavily gilded cloisonné.

Another artifact with only

limited connections to antiquity was a bird vessel on wheels. The exhibition

contains two such pieces-catalogue numbers 89 and 88. The former depicts a bird

with pigeonlike beak and ears, wings swept up at the sides, and a long tail

curling under to form a stabilizing element for the large wheels attached to

the sides. On its back, this curious creature supports a vessel that looks like

the upper section of an archaic zun.

Catalogue number 88 was constructed as a bird perched astride a pair of wheels,

bearing on its back a zun vase with debased

blade and taotie (饕餮) patterns. Taotie is the name given to the animal

face that was often depicted in two halves on either side of the casting ribs

on archaic bronzes. The bird body was patterned with feathers, and its spine

was ornamented with hooked flanges. The flanges resemble the decorated section

joints on archaic bronzes, but they are an incongruous feature here, for they

perform neither an illustrative nor a constructional function.

Where did this strange vessel

originate? During the Western Zhou periods, bronze zun were cast in the form of birds. They stood on two feet and were

balanced by a long tail curling under at the back, but they did not have wheels,

a feature illustrated only in catalogues of purportedly ancient bronzes. Xiqing gujian, for example, depicted a

splendid example in volume (juan) 11, and it is clear that such illustrations

acted as prototypes for bird zun with

wheels, made in both cloisonné and bronze in the Qing dynasty.

The Influence Of Illustrated

Catalogues

Throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties, there were two general

approaches to understanding the past. One involved written words and printed

images, the other actual objects, including surviving and excavated artifacts.

A combination of the two approaches had been used in the Song dynasty, when the

first catalogues of ancient objects were printed. At that time, a growing

interest in the material past led a number of scholars to collect ancient

bronzes, including those dug from the ground at ancient sites. Antiquarians,

officials, and the imperial family competed to purchase these powerful manifestations

of China’s long and unbroken civilization. Emperor Huizong was the greatest

collector of all and is said to have built up a collection of ten thousand pieces.

When good collections had been formed, proud owners sought to publish them, sometimes

in the form of illustrated catalogues. Among the best known are Kaogu tu (考古圖;

Researches on Archaeology with Drawings) compiled in 1092; Xu kaogu tu ( 續考古圖;

Continuation of the Researches on Archaeology with Drawings), published seventy

or eighty years later; Chongxiu Xuanhe

bogu tulu (重修宣和博古圖錄; Drawings

and Lists of Antiques) finished about 1123; Jinshi

lu (金石錄;

Collection of Texts on Bronze and Stone), published between 1119 and

1125; Xiaotang jigu lu (嘯堂集古錄; Records of the

Collections of Antiques of the Whistling Studio), written soon after 1123; and Lidai zhong ding yiqi kuanzhi fatie (歷代鐘鼎儀器欵識法帖;

Copies of Inscriptions on Bells, Cups, and Vessels throughout the

History of China), published in 1144.

Many of these texts were

reprinted in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Kaogu

tu, for example, reappeared in a popular edition in 1752. Pieces in the

exhibition such as catalogue 79 are similar to illustrations in that edition.

The overall form with a lid has its origins in such an object as that described

as a dui (敦), a sacrificial vessel

for grain. Nowadays, we would categorize such vessels as gui. The handles on catalogue number 79 have a more marked

resemblance to another object illustrated in the catalogue, with upright ears

or horns, curved fangs, and a pendant flange on the underside of the handle. As

is frequently the case with cloisonné, the makers of catalogue number 79 have

combined several ancient features and added contemporary elements. The ornate

gilded knop and pierced panels on its lid typify eighteenth-century metalwork,

whereas its enameled decoration contains archaistic elements and scrolling

flowers.

Changes in the academic climate

in the Ming dynasty meant that the study of ancient bronzes through archaeology

became less popular. Scholars relied instead on non-illustrated works devoted

to collecting and connoisseurship, which relied on descriptions of size,

weight, patination, and tone when struck. In the later Ming period, during the

sixteenth to seventeenth century, these manuals became more specialized in

their function as manuals on fashion and taste and have been described as

“handbooks of elegant living.” In this canon, cloisonné often had no

place. Indeed, an early Ming handbook, Cao’s Gegu yaolun (格古要論; The Essential Criteria of Antiquities)

published in 1388, pronounced that cloisonné objects were not appropriate for a

scholar of cool, reticent taste to study and were appropriate only for the

chambers of a lady. As described in this book (see Chapter 4), there were

exceptions to this view.

There is one Ming dynasty text

that has specific relevance to cloisonné enamel vessels, and that is the Xuande yiqi tupu (宣德儀器圖譜; Illustrated

Catalogue of the Ritual Vessels of the Xuande Period), which purported to describe

and illustrate ritual vessels for imperial altars and other destinations in the

palace in 1428. The text dates to about 1600, although the illustrations that

survive may not predate 1900. In spite of these caveats, the illustrations and

descriptions it contains correspond closely to a large number of Ming bronzes,

particularly incense burners.

During the Qing dynasty, the

study of illustrated texts became popular once more, and many catalogues were

published for private collectors. The Qianlong emperor was the most prolific

collector of all, gathering treasures from all over the empire. He modeled

himself on previous rulers who had amassed ancient relics, particularly jades

and bronzes. The ownership of physical manifestations of China’s long and glorious

history was one means by which rulers manifested their legitimacy, and as a

Manchu, Qianlong was conscious of the need to embody the values of national culture.

Furthermore, he sought to systematize the vast collection of palace bronzes

through the medium of printed illustrated catalogues that incorporated the

latest scholarship. To this end, he sponsored the production of books of

bronzes, the first of which was the series called Xiqing gujian, which was originally published between 1749 and 1755,

with a supplement in 1793.

Bronzes copied from woodblock

print illustrations sometimes showed features that did not correspond to

ancient objects but rather to line drawings in the catalogues. In the case of

some fake bronzes, this resulted in amusing misunderstandings of form or

decoration.

An illustration from Xiqing gujian illustrates the manner in

which bronze designs could be rendered in woodblock print illustration. The

overall background is of squared spirals, sometimes called leiwen (雷紋; thunder patterns) by scholars. Superimposed on the leiwen are bands of taotie masks. On the bronze zun

vessel shown in this figure are two bands of taotie around the body, and additional taotie face upward on the leaflike blades around the neck. The

features of the taotie appear highly

stylized and split into widely dispersed component parts. This, coupled with

its depiction in a scheme of raised lines, is an effect seen on many later

bronzes. At the base of the zun neck

are two dragonlike creatures, which confront one another on either side of a

central raised casting rib.

It seems probable that certain

items of cloisonné, especially those of imperial provenance, followed

conventions established for archaistic bronzes. In the case of cloisonné, however,

artisans adapted ancient styles very freely, often rendering archaic designs in

an abstract manner and incorporating non-archaic motifs on the same object. For

example, the square zun vase bears an

abstract pattern of hooked spirals in deep blue enamel on its body and a

bladelike decoration on its neck. The hooked spirals can be read as elements of

a taotie mask like that illustrated in

Xiqing gujian, but reinterpreted in

an ornamental manner so that they have lost a coherent meaning but still

reflect echoes of “ancient” style. Moreover, they were combined with

branches of scrolling flowers on the shoulder. The taotie can more clearly be recognized on the round hu vase. An overall systematized scheme

in deep blue enamel resolves itself into stylized masks by the inclusion of

black-and-white eyes and red whiskers. These simple additions render the scheme

readable.

Taotie masks were more rigorously observed on the square incense

burner, which is an ancient shape called fangding

that was current in the late Shang dynasty. On all four sides of the vessel are

taotie, with bands of confronting

dragons above them. These devices were somewhat embellished in a Qing dynasty

reinterpretation of the ancient form. Moreover, the vessel was customized with

an ornate openwork grille in the lid for incense smoke, on top of which is a

gilt-bronze Buddhist lion with its paw on a brocaded ball.

Bands of taotie and confronting dragons are found on the vase in catalogue

number 73, which copies an archaic vessel called a fang lei. In this instance the form imitated several features of ancient bronze quite

faithfully, including

hooked flanges, which would originally have ornamented the joins of a piece-mold casting, and animal

mask handles. But however

closely the shape was observed, the

bright colors of cloisonné enamels created an effect very different to that of old

metal.

On some items, elements of design in an ancient spirit were

effortlessly incorporated into contemporary schemata. The ruyi scepter has on its front side charming cloisonné scenes of

figures working in a landscape and large inset jade panels of dragons. The back

surface of the ruyi, by contrast,

bears a pattern of hooked volutes in deep blue bordered with red, whose source

is archaistic.

Incense Burners

Incense,

or more strictly speaking fragrance, was originally used in China as a form of

fumigation. It performed the function of dispersing insect pests while being

harmless to humans, and moreover it dispensed a pleasant smell. Artemisia, a

native plant that was readily available, was burned for this purpose at least

as early as the Zhou dynasty. Its dense clouds of fragrant smoke also served to

discourage mustiness and nasty smells. Starting in the Han dynasty, incenses

derived from woods such as camphor and sweetgum (liquidambar) were

imported from Southeast Asia. These substances could not be directly burned

like artemisia but were mixed with gum and burned on charcoal, and so

specialized utensils for incense were first developed.

From this time on, substances for incense use in China can

be divided into vegetable and animal fragrances. From the vegetable kingdom

came such fragrances as cassia, camphor, liquorice, and fennel; the animal

kingdom supplied such perfumes as musk and civet. Local plant and wood essences

such as artemisia were always cheaper than true incense. They were burned as

fragrances and also what Song dynasty texts described as “mosquito

smoke” to repel insects. This was essential during the humid summer months.

By the Song dynasty, the importation of

incenses and their use in domestic, scholarly, religious, and palace settings gave

rise to a widespread and lucrative trade. Incense was used in temples as an aid

to meditation and was also available for worshipers to buy and burn as an invocation

or prayer. It was employed to scent palace halls and people’s homes. Scholars

used it when practicing activities such as calligraphy and music or enjoying

antiques, especially when seated outdoors. Incense was considered luxury

commerce, for sale in upmarket shops in the best commercial districts. Very

expensive imported incenses such as myrrh or frankincense from Arabia were

available, along with aloeswood, dammar, gharu wood, ambergris, and sandalwood from

Southeast Asia. Vast quantities of aromatics were imported, and powerful

families controlled huge profits. One of the most active areas for business was

Fujian province, whose location in southeast China and long coastline favored

contact with the outside world and the development of maritime trade. In Fujian

the wealthiest Muslim merchant clan in the port city of Quanzhou controlled the

incense trade. The business was founded by an Arab or a Persian-born man called

Kuwabara (Chinese name Pu Shougeng, 蒲壽庚).

Pu Shougeng (d. 1296) was appointed superintendent of maritime trade by the

Song state and later served as the governor of Fujian province during the Yuan

dynasty. During the Ming dynasty, one branch of his lineage moved inland to

Yongchun, where incense is still processed today by traditional methods.

The formation of incense into sticks and cones was well known

by the Northern Song dynasty (960-1126), and from this time a different type of

receptacle was required for burning. The sticks or cones were stabilized in

beds of sand and ignited either in a flat, bowl-like vessel or inside a more

complicated utensil that allowed incense smoke to coil out through holes.

Instances of the latter style of incense burner included models of Buddhist

lions and lotus flower censers with lids, but the former bowl-like vessel is the

one most relevant to archaism. Although a simple dish or bowl could have been

used, more elaborate and decorative forms were preferred, and where better to

derive models for such utensils than from archaic bronzes, which were greatly

in vogue at the time? Several bronze shapes such as gui and ding lent

themselves readily to the new function. They also served as suitable central

utensils in the five-piece wugong

altar sets that were becoming a fixed feature for temples, palaces, and

shrines.

By the Yuan and early Ming dynasties, incense burners were

made in a wide range of shapes and in many media, prominent amongst which were

bronze, ceramic, and cloisonné. A distinctive style was that described in Xuande yiqi tupu as a “palace

censer in the form of a court official’s hat,” presumably because its

prominent, upright handles resembled the starched appurtenances of a mandarin’s

hat. As previously mentioned, Xuande yiqi

tupu was almost certainly not published until the late Ming dynasty, and

its illustrations were added even later than that. Nevertheless, the

illustration of a censer conforms to vessels made from the fourteenth century

on. Even if the catalogue was illustrated from preexisting vessel types, it is interesting

to chart how those vessels developed.

By the Yuan dynasty, censers “in the form of a court official’s

hat” were made with deep bodies and out-turned handles. The censer in the

exhibition has a well-conceived scroll of baoxiang

flowers (寶相花)

around the body, suggesting a possible connection with Buddhism. Baoxiang are composite flowers that

combine features of peony, lotus, chrysanthemum, and other flowers, and they adorned

decorative arts in all media. Baoxiang

is the respectful term used by Buddhists to address images of the Buddha, so

the scheme is often used on religious objects.

By the fifteenth century, cloisonné censers in “court official’s

hat” form look more like the illustration in Xuande yiqi tupu. The decoration of baoxiang flowers highlights a disparity between form and pattern

similar to that found on early Ming dynasty ceramics. For example, in the

imperial collection in the Palace Museum, Beijing, are two large blue-and-white

porcelain censers with rounded bodies and upright handles like the bronze

censers. One, dating to the Yongle period (1403-25), has a dense overall

depiction of rocks in the waves, similar to a design prescribed for imperial

robes. The other, dating to the Xuande period (1426-36), is painted with pine,

plum, and bamboo, the “Three Friends of Winter.” Cloisonné enamel is

more similar in appearance to over-glazed enamel-decorated porcelain than to

porcelain painted in underglaze blue. However, the development of enamels on

porcelain was not able to keep pace with the range of colors and brilliant

effects achieved by cloisonné in the fifteenth century. Although workshops were

set up at the imperial factory in Jingdezhen to experiment with color materials

allocated by the government from national warehouses, the achievement of a full

palette of colors on porcelain proved to be a slow and difficult process.

A related style of incense burner also developed during the

fifteenth century. This took its shape from an ancient bronze called li ding (鬲鼎), which had a body divided into three rounded lobes. The

bronze in turn derived from Neolithic pottery vessels that were made to heat

foodstuffs over a fire and whose lobed tripod legs resembled animal udders. The

early Ming dynasty cloisonné censers had two upright bail handles and bodies

whose lobing continued downward into the legs. Two incense burners in the

exhibition are shaped like this and bear the common decorative theme of baoxiang flowers. Catalogue number 149

has neat, plain handles, but on catalogue number 15 the handles resemble

twisted rope and may be a later addition.

Lobed tripod censers in cloisonné enamel were popular in the

Ming and early Qing dynasties. They were also commonly cast in bronze,

sometimes with the addition of partial gilding. Sufficiently large numbers of

this type of object exist to suggest that they were used in both religious and

secular contexts. The latter usage is reinforced by the décor

on a tripod, which depicts grapevines. During the Ming dynasty, scrolling

grapevines were also woven into and embroidered onto textiles and painted on

porcelain. In Europe such a pattern would suggest a connection with drinking

and wine, but in China it had come to represent the favorite theme of multiple

progeny. Bunches of grapes had many seeds, so the connotation was obvious. The

design came to China during the Tang period, carried there from the west along

the great Silk Road. In the Tang, a common ornament on the back of bronze

mirrors was lions among grapevines, neither one native to China. The incense

burner is a particularly handsome object with a wide, square mouth bearing an

archaistic squared spiral band, twisted rope handles, and a pierced lid. The

upper portions of the censer are lavishly gilded, providing a brilliant foil to

the colorful enamels.

By the seventeenth century, the lobed tripod shape was less

common in cloisonné, except in adulterated forms admixed with disparate

elements. Catalogue number 40 has three legs shaped like elephant heads with long

trunks, whereas the upturned handles are small in scale. The elephant theme,

mentioned above in connection with catalogue illustrations of bronzes, forms another

link with Buddhism.

Another type of incense burner made in cloisonné in the fifteenth

century had a deep, tub-shaped body and three small cabriole legs. Catalogue

number 14 was ornamented with baoxiang

flowers, and catalogue number 31 with a scrolling grapevine. A more elaborate and

almost certainly more expensive item was catalogue number 122, whose legs were

formed from caparisoned elephant heads and whose square handles were augmented

with clouds and classic scrolls. The enamels on this piece are brilliant in

color and the gilding extensive. The tub-shaped model had traveled even further

away than the lobed tripod censer from any connection with archaic bronze ding. Because of their simple, practical

shape, however, they continued to be manufactured throughout the Ming dynasty.

A seventeenth-century example is catalogue number 59, which accentuated a

general archaistic flavor with handles in the form of horned dragons. By

contrast, its decoration is naturalistic, with depictions of insects and

botanically accurate flowers. A circular yin-yang motif on the base suggests a

connection with Daoist worship.

To conclude this brief survey of incense burners deriving influence

from archaic forms, it is instructive to consider an archetypal ding bronze style with three tall,

tubular legs and a rounded body. During the Ming dynasty, this shape was often

reinterpreted in bronze and in cloisonné in rather a free manner. By the reign

of Qianlong, an altogether more robust attempt was made to simulate the ancient,

in both form and ornamentation.

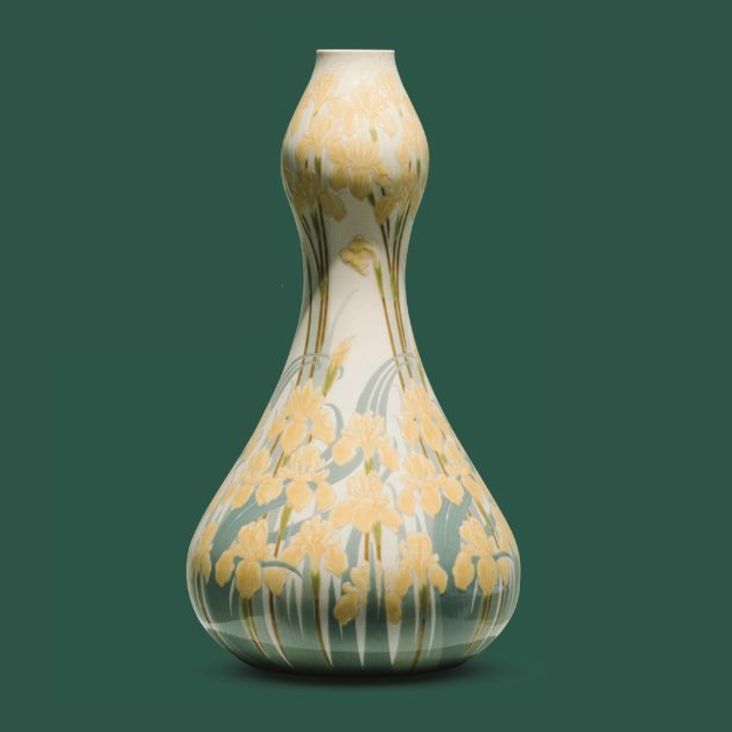

Vases And Jars

Owing

to their common function as single items and as part of five-piece altar

garnitures, vases and jars in the form of ancient bronze vessels zun, lei, and hu are common. The objects often display a mixture of influences,

deriving from both Bronze Age prototypes and decorative arts of more recent

dynasties. Rosemary Scott has pointed out in her discussion of archaism in

Chinese ceramics that artisans drew inspiration from many sources. Some related

back to ancient bronzes, whereas others dated to more recent eras. Thus, in the

Ming and Qing dynasties, elite Song dynasty styles were emulated. As early as

the late Ming dynasty and continuing during the Qing, admired sources from the

fifteenth century were copied alongside older models. Perhaps a similar

combination of old and newer effects occurred because cloisonné vessels such as

hu had forms analogous to ceramic

forms.

A closely observed ancient bronze shape is seen in the zun vessel in catalogue number 24, which

dates to the fifteenth century. The vase has heavy flanges in imitation of those

on piece-molded bronzes, but it bears a design of baoxiang flower scrolls that were a popular religious design with

no connection to archaism.

Stylistic features of the seventeenth-century square fangzun vessel are discussed above, and

at this point it is useful merely to consider how its detailed archaism was

repeated in the eighteenth-century round lei.

Both reproduced the silhouettes, animal head bosses, flanges, segmented panels,

and antique décor of bronzes.

Three hu vases

demonstrate a range of differing features. Catalogue number 69 matched the

shape, ring handles, and circular banded body of Han dynasty bronzes. Its

ornamentation of coiling baoxiang

flowers and dragons among waves provided a contrasting effect. The square-bodied

hu likewise reflects a Han dynasty form

but was embellished with contemporary patterns, including longevity roundels

and panels of birds, rocks, and flowers. A seventeenth-century hu vessel expressed a combination of

archaizing elements, because its profile and decorative sections more closely

resemble Song or Yuan dynasty bronzes than those of the ancient past. Similar

effects can be observed in ceramic objects, whose inspiration was likewise

derived from metalwork of the twelfth through fourteenth century. The same remarks

are true of the eighteenth-century cloisonné vessel, although in this case the

presence of large panels of inscriptions overshadowed its archaizing features.

The integration of Qing-dynasty styles with faint echoes of the past is visible

on a vase from the George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum in Springfield. The

form and handles refer to ancient bronze, but the auspicious design of

“one hundred deer” is closely comparable to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century

porcelain.

Champion Vases

An unusual form

of vessel became known in the Qing dynasty as a “champion vase,” a verbal pun on the

words ying

xiong (鹰熊; falcon

and bear), two creatures that are

supposed to be

applied to such pieces. The vessel took the form

of two cylindrical containers linked by ornamental twining beasts. Its origins date back at least as far as the Western Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 8), and twin vases fashioned

in jade and copying ancient prototypes were made

in the Song dynasty. By the Ming dynasty, they had become popular forms and were called nuptial cups by some scholars, which was an inaccurate term. During the Ming, double vases were made in jade, bronze, gilt bronze, bronze inlaid with gold and silver, rhinoceros horn, and cloisonné enamel. Ming objects tended to be modest in size and comparatively subdued in decorative terms, which made them suitable as scholar’s desk objects, perhaps even as brush holders.

One interesting example in the Victoria and Albert Museum is

a composite object made up of two Western Han dynasty bronze cylinders inlaid

with gold and silver. The archaic tubes were united to form a champion’s vase

by a bird standing on a beast, made in matching inlaid bronze in the late Ming

or Qing dynasty. It

has been suggested that this object, which defines archaism by reusing

genuinely ancient elements, is a type of “antique” favored by the

Qianlong emperor. Champion vases became very popular in the Qing dynasty,

when the form grew in size and the designs became complex and opulent. During

the Qianlong reign, many versions of the double vases were manufactured in cloisonné

enamel, and at this time the depiction of the creatures attached to their

surfaces were often lively and full of character.

This exhibition includes three seventeenth- to eighteenth-century

champion vases made in cloisonné enamel. The earliest in date is catalogue

number 85, which is made of two simple cylinders joined together on

one side by a gilt-bronze dragon and on the other by a bird. The dragon is a

hornless lizardlike type that can be found on many decorative objects in the

seventeenth century. Its depiction is full of movement, as its four feet clasp

the vessel and its head peeps over the rim. The bird on the other side, which

resembles a hawk with wings outstretched as if gliding on a thermal current of

air, is rather static by contrast. The cloisonné design on the cylinders is

made up of bands of sea creatures derived from a book called Shan hai jing (山海經; Classic

of Mountains and Seas). This ancient text was revived in popularity from the

late fifteenth century, and its illustrations of strange animals were used on many

art objects, especially porcelain and cloisonné. Both the basic form and

its applied beast and bird are archaistic, whereas the overall cloisonné

decoration is not.

Two later vessels date to the Qianlong period. Catalogue number

87 is composed of two adjacent hexagonal cylinders, shaped at top and bottom to

form vases. Linking the two is a mythical beast that has one paw on the base of

each vase and that supports a standing bird. The bird resembles a bird of prey

with hooked beak and talons, and it stands on one foot with its wings spread

out across the cylinders, as if on the point of flight. The cloisonné is

embellished with overall flower heads arranged in neat rows, a pattern that has

no reference to ancient bronze or jade. On catalogue number 86, two circular

vases are enhanced with the addition of lids. The vases are decorated with

twining baoxiang flowers, and they

have three conjoining beasts at foot, body, and lid. The beast at the foot is

of a standard type, but the bird perched on top of it has curiously stylized outstretched

wings that echo archaic bronze. The creature on the lid is a lively, muscular

dragon, an element not associated with the traditional combination of falcon

and bear.

Judging from the many and varied cloisonné objects brought together

for this exhibition,

it is evident that a significant proportion were inspired in both form and decoration by Chinese antiquity. Such influences were interpreted with a wide degree of latitude. Most often, the shape of archaic vessels

is what was copied, whereas the opportunities offered by cloisonné enameling gave rise to

decoration that often strayed far from genuinely ancient styles. Designs were often

distinguished by their modernity and utilized elements from contemporary decorative arts.

Chinese reverence for the past was expressed through the

imitation and reinterpretation of ancient objects. Understanding the past was a continual process, and each generation arrived at a

different view of the past using knowledge, materials, and societal filters common to their era. Thus, the Ming

view of the past differed from the Qing view, and this was reflected in the

forms of archaism in art, including cloisonné

enamel wares. Ming-dynasty cloisonné often showed a marked disjunction between form and

decoration, since archaic forms and designs were loosely interpreted or reinvented, whereas ancient shapes bore

contemporary patterns, and vice versa. During the Qianlong reign, archaism became a more strictly defined concept. In spite of this, many cloisonné

vessels continued to combine features copied directly from ancient artifacts or from

the printed catalogues of bronzes that circulated in ever greater numbers with

contrastingly abstract and decorative surface ornamentation.

© Bard Graduate Center, Rose Kerr.

One exception to this was the use of cloisonné as an element of jewelry. For example, in the Ming Wanli emperor’s Dingling tomb (constructed between 1584 and 1590) was a crown worn by the Wang empress. Constructed from lacquered bamboo and silk, it was ornamented with gold, gems, and pale blue cloisonné enamel.

Helmut Brinker and Albert Lutz, Chinese Cloisonné: The Pierre Uldry Collection (New York: Asia Society, 1989), 23.

Timothy Brook, Praying for Power: Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late-Ming China, Yenching Institute Monograph Series 28 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 1993).

Wen Zhenheng (文震亨), Zhang wu zhi jiao zhu (長物志校注; Treatise on Superfluous Things), written 1616-20, fol. 10 (Nanjing: Jiangsu Science and Technology Press, 1984), 357.

Susan Naquin, Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400-1900 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), xxx-xxxi.

Ibid., 156-58, 347.

Josh Yiu, “The Display of Fragrant Offerings: Altar Sets in China,” PhD thesis, Somerville College, 2005. This unpublished thesis concerns the evolution and development of the wugong.

Christine Lau (), “Ceremonial Monochrome Wares of the Ming Dynasty,” in The Porcelains of Jingdezhen: Colloquies on Art & Archaeology in Asia, no. 16, ed. Rosemary E. Scott, 92, 83-100 (London: Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, 1993).

Yiu, “Display of Fragrant Offerings,” 83.

Ch’en Hui-hsia (陳慧霞), “Bogu yu shenghuo” (Antiquarianism and Life), in Gu se: shiliu zhi shiba shiji yishu de fanggufeng (古色:十六至十八世紀藝術的仿古風; Through the Prism of the Past: Antiquarian Trends in Chinese Art of the 16th to 18th Century) (Taipei: National Palace Museum, 2004), 29-30.

Chang Lin-sheng (張臨生), “The National Palace Museum: A History of the Collection,” in Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, ed. Wen C. Fong and James C. Y. Watt, 3-26 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996).

Reported and illustrated in Chang Kwang-chih and Xu Pingfang, The Formation of Chinese Civilization: An Archaeological Perspective, ed. Sarah Allan, 195-96 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press; Beijing: New World Press, 2005).

Lau, “Ceremonial Monochrome Wares,” 94.

Liang Sui (梁穗), ed., Jingdzhen chutu Yuan Ming guanyao ciqi (景德鎮出土元明官窯瓷器; Yuan’s and Ming’s Imperial Porcelains Unearthed from Jingdezhen [sic]) (Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 1999), 132, 155.

For example, the roof ridge of the upper Guangsheng temple at Hongdong in Shanxi province, constructed in 1452, was ornamented with sacred creatures, including two white elephants bearing sacred jewels; see Rose Kerr and Nigel Wood, eds., Ceramic Technology. Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, pt. 12. Series initiated by Joseph Needham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 498.

A Western Zhou-dynasty bird zun from the cemetery of the Jin lords in Shanxi province is illustrated in Chang and Xu, Formation of Chinese Civilization, 192.

A Qing-dynasty bronze bird zun with wheels is illustrated and discussed in Rose Kerr, Later Chinese Bronzes (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1990), 77-78.

In Chinese ten thousand generally represents an enormous number.

See Kerr, Later Chinese Bronzes, 14-28, for a discussion of Song- to Qing-dynasty texts on bronzes.

R. H. Van Gulik, Chinese Pictorial Art as Viewed by the Connoisseur (Rome: lstituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1958). Craig Clunas, Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991), is devoted to this genre.

Quoted in Brinker and Lutz, Chinese Cloisonné, 28.

Kerr, Later Chinese Bronzes, 18-19, outlines the arguments and the scholarly debate.

Jessica Rawson, “The Qianlong Emperor: Virtue and the Possession of Antiquity,” in China: The Three Emperors 1662-1795, ed. Evelyn S. Rawski and Jessica Rawson (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2005), 272.

Yang Zhishui (杨之水), “Lianhua xianglu he baozi” (蓮花香爐和寶子; Lotus petal censers and incense burners), Wenwu 2 (2002): 70.

Wang Lianmao and Ding Yuling (王連茂,丁毓玲),Chongfan “guangming zhi cheng” (重返 “光明之城”; Return to the City of Light) (Fujian: Quanzhou Maritime Museum, 2000), 179.

Illustrated in Palace Museum, Beijing, Gugong ciqiguan · xiabian (故宫瓷器舘·下编; Ceramics Gallery of the Palace Museum), part 2 (Beijing: Purple Forbidden City Publishing House, 2008), 283; and Palace Museum, Beijing, Mingchu qinghua ci (明初青花瓷; Early Ming Blue and White), vol. 2 (Beijing: Purple Forbidden City Publishing House, 2002), 230-31.

Kerr and Wood, Ceramic Technology, 619.

Joseph Needham includes a lively account of the central role of incense and incense burners in Daoist ritual in Joseph Needham and Lu Gwei-Djen, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality. Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, part 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974), 128-34.

Rosemary E. Scott, “Archaism in Chinese Ceramics,” in International Colloquium on Chinese Art History, 1991—Proceedings—Antiquities, part 2 (Taipei: National Palace Museum, 1992), 497-518.

James C. Y. Watt, Chinese jades from Han to Ch’ing (New York: Asia Society, 1980), 156-57.

Philip K. Hu, Later Chinese Bronzes: The Saint Louis Art Museum and Robert E. Kresko Collections (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2008), 175-81. Hu illustrates and discusses a fine Qing-dynasty champion vase in the collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

Kerr, Later Chinese Bronzes, 74-78.

Rawski and Rawson, China, 291, 443.

Chen Ching-kuang (陳?光), “Sea Creatures on Ming Imperial Porcelains,” in The Porcelains of Jingdezhen: Colloquies on Art & Archaeology in Asia, no. 16, ed. Rosemary E. Scott (London: Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, 1993), 101-22.

Hsü Ya-hwei (許雅惠), “Xigu yu dianfan” (習古舆典範; Versed in Antiquity and Modeling the Past), in Gu se: shiliu zhi shiba shiji yishu de fanggufeng (古色:十六至十八世紀藝術的仿古風; Through the Prism of the Past: Antiquarian Trends in Chinese Art of the 16th to 18th Century) (Taipei: National Palace Museum, 2004), 88.