Originally published in Thomas Hope: Regency Designer, edited by David Watkin and Philip Hewat-Jaboor, New Haven and London: Published for the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, New York by Yale University Press, 2008.

Thomas

Hope drew much inspiration for his own furniture, fashionable costume, and

interior design from

a detailed knowledge of antiquity. His scholarly aesthetic,

however, was no mere antiquarian pursuit, no mere revival

of classical taste. Grander and more complex than these, Hope’s vision blended ancient with

modern, familiar with exotic, classical with Oriental, nature with culture, art with morality, and life with death. At Duchess Street

Hope the alchemist

melded together compound elements to forge a new and eclectic whole. We see his genius at work with the room he called the Lararium

and its piling up of objects representing comparative religions; we see it again in the Hindu and Moorish pictures and furnishings of the Indian Room and in Hope’s Regency-Pharaonic

designs and the sacred eschatology of the Egyptian Room; and we see it in the Greek

temple architecture of the Picture Gallery. Then

there was the Aurora Room designed

around a marble sculptured group of Aurora (Dawn) abducting Cephalus. In Hope’s outline engraving

for

his book Household Furniture, this sculpture appears as a paradigm

of refinement in modern taste, carved from white marble in

Rome by John Flaxman, the leading British sculptor of the day. And yet its altarlike base evokes the setting of an ancient cult image and thus seems

to blur the boundary between

the

contemporary secular world of the Regency salon and the ancient, sacred temple. A shrinelike interior was further suggested by the furniture and fittings and from the carefully selected symbolic

imagery of the room ‘s plaster

frieze and other ornament. Most striking, perhaps, were the azure, black, and orange curtains that

lined the walls. At the center

of each long wall these

draperies parted to reveal mirrors that reflected reverse images of the sculpture. The colors of the room, in Hope’s words,

were intended to evoke

“the fiery hue which fringes the clouds just before sunrise.” A classical dawn, answering the one personified in the sculpture, is summoned by Hope’s

phrase “rosy-fingered,” borrowed from Home r. To see this poetic attempt at capturing nature simply as a neoclassical device would be to miss the timeless

romance of not only this but of all Hope’s interiors.

Flanking Flaxman’s sculpture were two glass caskets, each one containing a velvet cushion.

On one cushion there rested

a marble

arm, which was said to have been acquired in Rome but thought to come from one of the human Lapiths doing battle

with Centaurs in the south metopes of the Parthenon. In

the other showcase was a stalactite, again from Greece

but this time from the

celebrated cave at Antiparos, which had been remarked

upon by the French ambassador to Constantinople, the Marquis de Nointel,

who had traveled in Greece in 1670-80. Hope

had himself made a

drawing of the cave, depicting it as a natural dome sheltering the plantlike forms of the giant, columnar stalactites

within. A piece of nature’s own architecture was set beside a fragment from the greatest man-made

building of antiquity, and

in this juxtaposition we find an epitome

of Hope’s pictorial and intellectual landscape. Art and nature

meet and are enshrined as equal contributors to the

romantic classicism of the Duchess Street interiors.

Art was similarly married to nature in the house and

grounds of the Deepdene, the country home and estate in Surrey that Hope bought in1807. There, for example,

was the “Hope”

itself, a natural

bowl in

the landscape that had been developed in the

seventeenth century by a

previous owner, Charles Howard, as a garden with terraces descending like the seats

of a Greek theatre. This feature, described

by John Aubrey in his book on the antiquities of Surrey, must have attracted Thomas

Hope

to the place by its name. He was to echo this Theatre of Nature

with a Greek-style Theatre of

the Arts in the small

mock

auditorium he attached

to the Sculpture Gallery at the Deepdene. In place of a seated audience

he planted its steps with classical heads and cinerary urns in rows.

Both at Duchess Street and at the Deepdene,

there is poetry in

the setting out of his collections

that distinguishes Hope’s from

other comparable house

museums in contemporary London, notably those of Charles Townley and the 1st Marquis of Lansdowne,

who both died in 1805. Lansdowne decorated the formal Adam interiors of his Mayfair

mansion with ancient marbles

in a conventional neoclassical fashion,

but he failed in his own lifetime to achieve his scheme for an additional

grand gallery. Townley too entertained grand

designs for displaying

his more extensive collection but

was forced in the restricted rooms of his house at Park Street, Westminster, to

adopt a pinched Picturesque. He had been amassing his collections of sculpture, vases, and other antiquities since he first visited Italy in 1768

on

the first of

three Grand Tours. His vast archive of documentary papers and drawings now in the British Museum testifies to the sustained interest that he took not only in his own collection, but also those of other collectors in London and elsewhere in Britain. Visiting in February 1804, Townley was

one of the first to see Hope’s newly arranged London residence, and he left us a list of the sculptures that he found there. To this simple document Townley appen ded a rhyming couplet that seems, rather nastily, to betray a touch of jealousy:

Something there is more needful than expense, and

something previous ev’n to taste … ‘tis sense.

Closer to the peculiar romance of Hope’s interiors are those of Sir John Soane, who was influenced by Hope, as indeed was the banker, poet, and conversationalist Samuel Rogers. Rogers went to Hope’s

house for inspiration in arranging his own collection of Greek vases and casts of

the Parthenon frieze as a setting at 22 St. James’s Place for his celebrated candlelit evenings of convivial Table Talk. Of all contemporary establishments, only Soane’s home miraculously survives, with the collections intact, at

Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Its witty juxtaposition of contrasts, artful use of mirrors, pictorial setting of objects, such as vases in columbarium niches, the necromancy of its Egyptian

mummy sarcophagus, the eclectic mix of archaeological cultures elegantly combined

in the unifying aesthetic of Regency classicism, all serve to remind us

of what we have lost at Duchess Street, ruthlessly demolished in 1851 by Hope’s son and heir, Henry Thomas.

Although the

house is long gone, something of its spirit can be found

in Anastasius, Hope’s novel, which provides a literary

parallel for the Duchess Street experience. The

young Greek of the story

explores his adolescent emotions as he discovers the natural and man-made world

during travels that take him through Turkey and the colorful dominions of the

Ottoman Empire—Greece, Egypt, and Syria. Anastasius was a window

through which Hope’s readers could enter a world that was both vast and

utopian. It was a world of fancy dress, which he would re-create in fashionable

interiors occupied by people who dressed the part. Here is the essential

purpose not only of Hope’s book, but also of his interiors. Duchess Street,

with its thematically arranged rooms, all on the upper floor approached by a

grand staircase, functioned as a theater in which the make-believe lives of

himself, his family, and their social set were acted out. Hope was actor,

impresario, scenery and costume designer, who, in his books on dress ancient

and modern, showed his guests what to wear. He commissioned several fancy-dress

portraits of himself and his family. In 1798 Sir William Beechey painted

one of Hope newly returned from his travels and decked out in Turkish dress.

This mature Anastasius was, by 1824 at least, suspended in the staircase hall

at Duchess Street to greet guests upon arrival.

Contemplating Hope as collector and antiquary, it helps to

keep Beechey’s portrait of him in mind, the defining image of Hope as a visitor

to the past, a foreign country. This was not the conventional souvenir of the

Italian Grand Tour set in Rome, where “Signor Speranza” would have been

depicted in fashionable European dress with some token souvenir of classical

statuary. Instead “Ümit Bey” stands on the terrace of a Turkish palace, and in

the background rise the dome and minarets of a mosque. The dress and the

setting are from contemporary Ottoman Turkey, where Hope had resided and

traveled and which he had himself drawn. In Anglo-Turkish relations, the year

1798 was an annus mirabilis. In that

year Admiral Lord Nelson defeated the French at the Battle of the Nile and thus

dealt a mortal blow to French efforts to capture Egypt from the Ottomans. In

that same year, the British were to capitalize on their new-found favor at

Constantinople by dispatching Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, at

the head of an embassy to the Turkish capital. Ultimately, however,

Beechey’s portrait references more than the particular culture it represents.

It is not only Turkish but is also belongs to a larger field of

eighteenth-century fascination for the exotic, epitomized in the bringing to

London in 1774 of Omai, the native of Tahiti, and his portraits by Joshua

Reynolds.

By contemporary standards, Hope’s own travels were

extraordinary. Most Europeans of his time did not go beyond Italy, where, for

those in need of exotica, Naples and Sicily came to represent the fringe. At

the age of eighteen in 1787, he embarked on the first of a set of journeys that

would occupy him off and on for the next ten years and take him to Turkey,

Egypt, Syria, Greece, Sicily, Spain, Hungary, Palestine, Portugal, France,

Germany, and ultimately back to England. There, in 1795, other members of the

Hope family of wealthy Dutch bankers (of Scottish descent) had settled in

Hanover Square, London, to escape Napoléon’s invasion of their homeland. Travel

opened Hope’s eyes to a world where ancient past and foreign present fused into

one eclectic “other.” No book, no picture or household interior could

substitute for the experience of travel itself for, as Hope himself puts it,

not even in “the least unfaithful, the least inaccurate even, such as Stuart’s

Athens, Revett’s Ionia, no adequate idea can be obtained of that variety of

effect produced by particular site, by perspective, a change of aspect and a

change of light.”

Hope

was himself a considerable draftsman, and a record of his travels in 1796 and

1797 is preserved in five volumes of drawings now in the Benaki Museum in

Athens. The drawings are a compendium of architecture, ruins, landscape,

sea and river craft, costume, interiors, and antiquities. Among these last is a

study of the central block of the east frieze of the Parthenon as yet

uncollected by Elgin and still resting on the ground as part of a parapet

wall. In his crisp outline drawing. Hope shows the figures of

the frieze standing in their classical costumes or seated on Greek furniture.

Zeus, as father of the gods, occupies a throne with an armrest supported by a

sphinx, an ancient forerunner of Hope’s own zoomorphic Grecian furniture. Hope

sets up a conversation between this ancient gathering in stone and the four sailors in modern Turkish costume, who sit

on the ground smoking pipes after taking tea. With their backs to the viewer, they face the frieze,

and one of them actually

points toward it. Meanwhile, one of the seated gods (Hera) and one of the standing figures look out from the frieze, not at any particular spectator but with a gaze that transcends this fleeting

moment. So at Duchess

Street the many ancient gods and heroes

frozen there in marble

would look coldly upon the modern

world with unseeing eyes, unmoved

by the admiring gaze of those gathered to view them.

Collecting Sculpture in Italy

Before his arrival in London in January 1795, Hope seems not

to have conceived of making a collection, but before the year was

out,

he had left London for Rome in the

company of his brothers,

Henry Philip and Adrian Elias, expressly, it seems, for the purpose of buying classical sculpture. No doubt they had witnessed

in England the well-established habit of forming a sculpture gallery,

and this experience had inspired Thomas and his brothers

to a new venture. In Rome of the 1790s, there were two principal sources through which classical sculpture could be bought.

On the one hand, there were the collections of the old Roman aristocracy who had fallen on hard times, and there were licensed

excavations on the other. Both sources could be accessed

through a community

of dealers, which included several British members, notably

Thomas Jenkins, Gavin Hamilton, James Byres, and the Irish

painter Robert Fagan. There were also the restorer-dealers who would themselves

renovate a statue and sell it on. A particular favorite of Thomas Hope was

Vincenzo Pacetti, who restored the Hope

Asclepius, said to come from Hadrian’s Villa. It is one of few Grand

Tour sculptures to make the round trip between Rome and London, leaving England

in the 1950s, when it was bought for a private collection in Rome. In 1796

Henry Philip bought from Pacetti the Dionysos,

along with an archaistic statuette known then as Bacchus and Hope, an irresistible subject for a collector of

the same name. It was said of the piece that it was acquired from the

Aldobrandini Palace on the Quirinal. Adrian Elias bought the Roman copy of the Pathos (Desire) by Skopas, which had

been restored as a copy of the Sauroctonus

Apollo by Praxiteles and which, before 1532, appears to have been in the

collection of Francesco Lisca. The brothers Hope also made joint purchases,

such as in 1796 that which came from the restorer Giovanni Pierantoni,

namely the Antinous statue. There

was also a couple restored as Apollo and the boy nymph Hyacinthus and a

statue of Apollo with bow and quiver. Whoever the purchaser was, all the

sculpture bought on this shopping trip to Rome would find its way into Thomas

Hope’s Duchess Street mansion.

Further purchases

were made from Prince Sigismondo Chigi, who had acquired sculpture from excavations

at the imperal villa of Antoninus Pius at Laurentum, south of the Roman port at

Ostia. These include the greyhound bitch and dog, which may be compared

with the pair in the Townley Collection of the British Museum and with that in

the Vatican. Most probably also from the site of the same imperial villa

came a portrait of a female of the Julio-Claudian court, possibly Agrippina or

Livia. With it came the portraits of Antoninus Pius and of Faustina Maior.

The whereabouts of the former is unknown; the female bust is in the Royal

Ontario Museum, Toronto.

Two of

the grand highlights of the Hope collection came from Tor Boacciana on the

outskirts of Ostia, where the Irish painter and antiquary Robert Fagan

conducted excavations. These are the over-life size Athena and the Hygieia.

Their discovery is described, in a note quoted by Waywell, as “among the ruins

of a magnificent palace, and thirty feet below the surface of the ground,

broken into fragments and buried immediately under the niches in which they had

been once placed” The Athena is thought to be a Roman copy of the second

century A.D., based on a lost Greek statue made around 440-420 B.C. The

putative Greek original may be attributed to one of the pupils of Phidias,

either Alkamenes or Agorakritos. The Roman copy was extensively and

impressively restored as a variant of the Athena

Parthenos, another Phidian creation. Sadly, much of the restoration was

removed after the Hope sale of 1917, at which this statue fetched £7,140, the highest price of all.

It was bought

by Agnew acting for Viscount

Cowdray. When it was sold again at Sotheby’s in 1933, the value had plummeted

to a mere £200. This fall in value is eloquent

reminder of the economic depression that blighted America

and Europe in the after math of World War I and,

indeed, a shift in taste away

from restored

Roman copies and toward

such Greek

originals

as the market provided. The Athena later passed into the estate of

W. R. Hearst at San Simeon and, after his death, to the Los Angeles County Museum.

The

other star piece in Hope’s collection was the Hygieia, another Roman statue that has been dated to the second

century A.D. and a copy of a lost Greek original probably of

the first half of

the fourth century B.C. Like the Athena, her head is her own and,

with similar inlaid

eyes and near equal stature,

this goddess of healing

formed a pair with the goddess of wisdom. She was bought at the Hope sale in 1917 for £4,200 by Spink acting for Sir Alfred Mond, later Lord Melchett. At

the Melchett sale of 1936, the price had fallen to £598 10s, when she was purchased

by Hearst and donated

to the Los Angeles County Museum in

1950.

Hope at Home

In

1799 Hope bought the Duchess

Street house, where his burgeoning collection was to be displayed. It

is sometimes said that the acquisition of the house did not, as we might expect, detain him in England, and later that year he was again in Greece

planning a tour of the Peloponnese with the Levant Trading

Company’s consular agent in Athens, Procopio Macri. It appears, however, that the Hope of this excursion was his younger brother Henry Philip. Late in 1799, it was he who carved

his name and initials on a column at Delphi, having already in June of that year visited the Troad

in northwest Turkey.

Thomas Hope, meanwhile, was taking

advantage of the home

market in antiquities. He

bid successfully for sculpture at the sale of

the Duke of St. Albans’s

pictures and antiquities at Christie’s on April 29, 1801. Earlier at Lord Bessborough’s sale at Christie’s on April7, 1801, he

had made other purchases. William Ponsonby, 2nd Earl of Bessborough, had died in 1793, and as is so

often with those formed

in the eighteenth century, his collection

did not long survive him. Among a clutch of items Hope purchased at this sale was

the Ganymede, said to have been found in 1767 in

the Campus Martius in

Rome and bought from the Villa Albani. Also at Bessborough’s sale, Hope acquired

a colossal porphyry foot. It was fashionable at the time to

have a big foot, and Sir William Hamilton had presented his to the British Museum in

1784.

Sir William Hamilton’s return

to England in 18oo, at the end of a thirty-six-year residence

in Naples, was to provide the opportunity for further

purchases. Hope ‘s acquisition of Hamilton’s

vases is well known, but his purchase of sculpture from Hamilton

was forgotten until recently. Hope bought sculpture at Hamilton’s sale of pictures and sculpture in March 1801, where he competed

in the bidding with Frederick Howard , 5th

Earl of Carlisle. Hope’s

purchases included a Roman statuette in archaic Greek style of Dionysos, which he illustrated in his 1809 book Costume of the Ancients

restored with the Dionysiac

staff, or thyrsus, in one hand and a drinking cup in the other. It was said to have been found in Rome. Once it belonged to Lord Melchett, but its present location is unknown. There was also a Roman archaizing statuette of a goddess

holding a lotus flower in one hand and an egg in the other. She was said to have been excavated near Capua. Such archaizing

sculpture was fashionable

in Hope’s day and had been so since Johann

Joachim Winckelmann

publicized the several

examples still to be found in the Albani collection

in Rome. To Hope and his contemporaries these sculptures were not seen as the Roman revivals of earlier Greek styles, as they are now recognized, but were authentic Etruscan

or early Greek productions viewed

as sculptural examples of that

noble simplicity found in archaic

vase paintings. From a later period of Greek art

comes a statuette of Cupid embracing

Psyche

that remains

lost; a basalt Egyptianizing lion said to come from the ruins of the Villa Jovis on Capri, and a porphyry

head of Nero

mounted on a bust of

gilded

bronze

by Luigi Valadier. Another

portrait bust,

thought

to have belonged

to Cicero and excavated in the ruins of his

villa at Formiae near Gaeta, is perhaps

to be identified with a fine terminal bust of

Meleager. Hope also acquired a marble cinerary urn carved

in the form of a covered basket, which is shown on a tripod stand in the Picture Gallery at Duchess Street.

Finally, there is the black basalt head mounted on a bust of rosso

antico that has entered the collection

of the British Museum. Thought by Hamilton to resemble Cicero, it is almost certainly an

eighteenth-century forgery.

The French occupation of Italy in 1798 would keep British travelers out of the country, until the Treaty of Amiens

in 1802-3 brought a respite in hostilities that allowed Hope to make his way to Rome and eventually to Naples. In Rome part of his purpose was

to negotiate the release of some of the sculpture

purchased in the previous decade and confiscated by the French before it could

be shipped to England. In Naples he acquired a fine

statue of Aphrodite, about which we are unusually well informed owing to recent discoveries in the

Townley archives of the British Museum. These concern an Aphrodite with drapery

around the lower part of her

body in the so-called Syracuse form of the Medici type. She is said by Charles

Westmacott to have been discovered at Baiae, the pleasure park of the Emperor Nero on the Bay of Naples. The statue was presented

to Athens in 1920 by the Greek shipbroker Michael

Embeirikos, who had acquired

her at the auction sale of the Hope collection in 1917.The Westmacott provenance was to be repeated in

subsequent mention of the statue but is now shown to be false. In fact it came from the ruins of ancient

Minturnum on the banks of the River Garigliano, the ancient Liris on the border between Campania and Latium. It was restored

with a new head by Carlo Albacini, a gifted pupil of the great restorer Cavaceppi.

Exactly how Hope came upon the Aphrodite is not known,

but it seems certain that he snapped her up on the Naples leg of his Italian journey of 1802-3. In May 1803 he was sensibly back in

Paris and therefore able to cross the channel to safety, when the peace

with France was broken in May. He would not again venture abroad until 1814-15, when the Hopes wintered

in Paris, but they were once more forced to retreat, this time by Napoleon’s escape from Elba. After his final

defeat at Waterloo, the Hope family set off for Europe once more, and after a slow and difficult journey,

during which they were robbed, they reached Rome in April 1817. Their stay was

cut short, however, by an even greater misfortune, the death of their second son, Charles, at the hands of quack doctors who attended his illness.

During the years spent in England between 1803 and 1814, Hope had much to busy himself

with, arranging and promoting the display of his collection, first at the London mansion

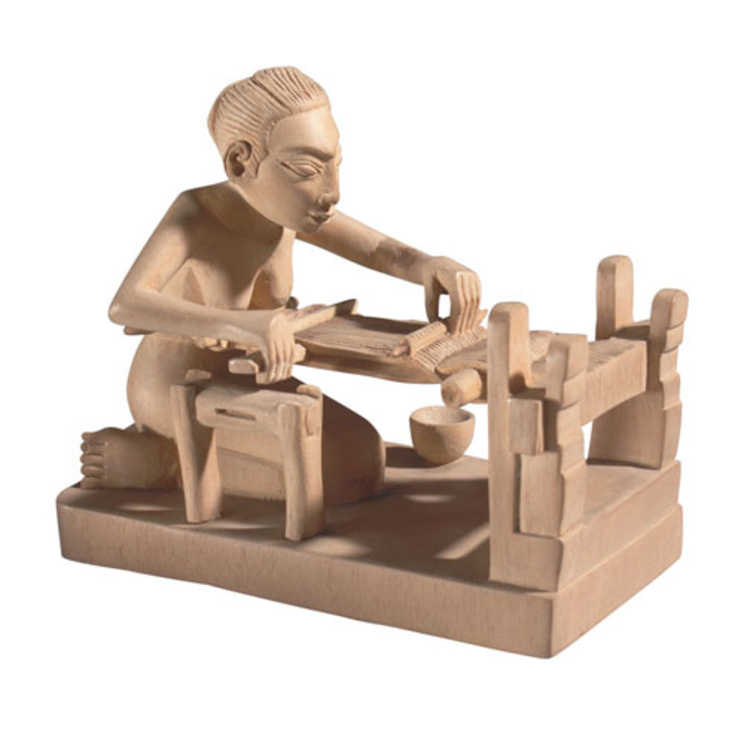

and later at the Deepdene. At Duchess Street Hope’s classical sculptures were arranged

principally in the Statue Gallery,

while others were to be found in the Picture

Gallery, with its architectural detailing quoted from famous Athenian

monuments and in the so-called

AnteRoom. In the Statue Gallery,

walls were left plain and painted yellow to provide

strong contrast and to bring out the contours of the sculptures. The ceiling of the room was

coffered like a Greek temple

and had three openings to provide light from above in the manner

that was to become preferred

in nineteenth-century sculpture galleries. The sculpture

itself, at least to begin

with, was arranged symmetrically along the long walls with statues, statuettes, busts, and cinerary

urns placed to match one another, like facing like. Subjects too were matched,

and thus we find Pothos (Desire) facing Aphrodite, and a bust of the Antonine emperor

Lucius Verus opposite

Antoninus Pius.

As

part of his architectural

transformation of the Deepdene, Hope developed there a second Sculpture

Gallery that extended

westward from the main house. This formed part of a

picturesque complex of spaces, including a great Conservatory that ran parallel to and connected

with the Sculpture Gallery

and, to the west of these two rooms, the so-called Theatre of Arts. In the winter of 1824-25,

Hope removed to these newly laid-out rooms a large part of his classical sculpture

collection, and so upon

his death in 1831, the collection was divided between the two houses.

His heir was his eldest son, Henry Thomas Hope, also a serious

collector of sculpture

and one who had ideas of his own. Soon after

his father’s death, most of the sculpture

was returned to Duchess Street from the Deepdene, and the

Sculpture Gallery there was used for other purposes. Henry shared his father’s sense of

self-importance but had not inherited

Thomas Hope’s sense of style.

He carried out extensive

rebuilding and refurbishment at the country house, transforming it from a rambling picturesque and in parts neo-Gothic villa into a more formal and grandiose Italianate palace. In 1849 he moved the entire collection of antiquities to the Deepdene, two years

before the Duchess Street mansion was demolished. A

sale of vases and other miscellaneous antiquities in 1849 was no doubt prompted by this

move. Most of the sculptures were accommodated in

the entrance hall, with the great pieces, modern

as well as ancient, set up in its cavernous arches.

The Sculpture Gallery does not appear to have been

reused and, indeed, was probably demolished before the 185os were out.

Greek Vases

Turning from his sculpture, and thus avoiding

the sad decline of the Hope fortunes

that preceded its sale in 1917 and the eventual demolition of the Deepdene in 1969, let us explore

how Hope acquired his Greek vases, which were both a prominent

feature of display

in the Duchess Street mansion

and a great influence upon his own design of furniture

and costume. Hope’s acquisition of Sir William Hamilton’s second collection of Greek

vases in 1801 was

a significant event in the development of the Hope style. The ancient painted

pots made for everyday use that we commonly call Greek vases had been found in Italy at

least since Roman times and since the Renaissance were highly valued

as curiosities by collectors and artists. Although these vessels were previously thought

of as Etruscan, it was gradually

realized in the eighteenth century that they should properly be

called Greek. Although there had in antiquity been an Etruscan

ceramic industry that produced

its own version

of Athenian black- and

redfigured painted pottery, the Etruscans, it must be said, were better at

bronze-casting, goldsmithing, and carving engraved

seal stones than they were at potting.

The best vases found in Italy were not Etruscan, therefore, but had either been imported in antiquity from mainland Greece or produced in

southern Italy, where Greeks

had founded colonies in what they themselves called Magna Graecia. In the ancient

regions of Campania, Apulia, and Lucania and on Sicily, Greek settlers had brought

their own pottery production with them and founded

the South-Italian branch of an industry that was to flourish and persist deep into the fourth century B.C., when the mainland Greek workshops of Corinth and Athens that inspired it had long ceased to dominate the market.

Sir

William Hamilton was resident in Naples as the British diplomatic representative from 1764 until 1800. During

that time, he had ample opportunity to collect

antiquities, gathering such fruits as he was able to pluck from officially restricted royal excavations in the ancient cities of

Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Older than the towns buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79 were Greek and other tombs scattered

through the countryside

of southern Italy. Hamilton

acquired vases directly from these tombs or from existing collections. Hamilton

was by no means the first to collect

vases, and a number

of prominent Neapolitan

intellectuals had anticipated his passion for them as curiosities of ancient handicraft and as a picture

book of ancient

life and beliefs. Hamilton, however, made his own contribution to the understanding of Greek vases by

promoting them as examplars

of ancient art, described by Winckelmann, the greatest art historian of his time, as “a treasury of ancient drawings.”

Hamilton’s promotion of vases manifested itself

in three principal ways: first, by publishing his first vase collection

in four sumptuous volumes

that collectively make up what may arguably be judged the most beautiful

book of the eighteenth

century; second, by successfully placing his first collection of vases, and indeed other antiquities, in the British

Museum, where it represented the national holding

of such objects

and laid the foundation of the museum’s

current identity as a great showplace of art and antiquity; and third, in the influence

that his publications had on contemporary taste, especially on the new pottery

of

Josiah Wedgwood

and Thomas Bentley,

and ultimately on

the Regency Greek Revival,

of which Hope was

to become a leading luminary.

Hamilton sold his first collection to the British Museum in

1772 and in so doing greatly increased

the value of the trade in vases. He would afterward complain that he had undersold the collection, but like an addict aware of the dangers of his own weakness,

he resolved to give up the vases and succeeded

in doing so for seventeen years. Then in 1789 the compulsion took hold of him once

more. How

it came about is explained

in a letter to his

nephew and fellow collector Charles Greville, an impecunious

scion of the House of Warwick.

Sir William’s own words

tell

how it was that the Hope collection of Greek

vases, as it would become, was first conceived:

A treasure of Greek, commonly

called Etruscan, vases have been found within these twelve months,

the choice of which are in my possession, tho’ at a considerable expense. I do not mean

to be such a fool as to give or leave them to the British Museum, but I will contrive

to have them published

without any expense to myself, and artists and antiquarians will have the greatest obligation to me. The drawings on these vases are most excellent and many

of the subjects from Homer. In short, it will show that such monuments of high

antiquity are not so insignificant as has

been thought by many, and if I choose afterwards to dispose of the collection (of more than seventy capital vases)

I may get my own price.

The impulse for this new interest in vases had been a series of

lucky strikes by people we would today call tomb robbers on land in

the neighborhood of Nola, S. Agata dei Goti, Trebbia,

Santa Maria di Capua, Puglia,

and elsewhere.74 In mentioning seventy vases, Hamilton was speaking of the

best figured vessels

in his collection. By the time he embarked

his collection for England in 1798,

the total number of figured

and nonfigured vases together had risen to more than a thousand. From the start, Hamilton

was forced to see his second collection as a financial

speculation. Never a wealthy man, he had mounting

debts that were increased by ambitious improvements to

his Naples residence, Palazzo Sessa, and the expense of keeping Emma Hart, who had lived

with him as his mistress since 1786. The eventual sale of the collection to Hope in 1801 was the outcome of a protracted attempt

to sell the collection at a profit to the monarchs of

Russia and Prussia and to his kinsman William

Beckford.

From the start, Hamilton

planned to publish his second

collection as he had his first. He did not, however, wish to repeat the expense

and worry of his first attempt, caused in part by his employment of

the brilliant but unreliable Pierre François Hugues, who liked to go by the name of Baron d’Hancarville. Hamilton did, however, need someone to oversee the book’s

production,

organize the drawing of the vases, the engraving

of the drawings, and the drafting of the commentaries that accompanied the engravings. The texts were to be supplied by Count

Italinsky, the Russian consul in Naples,

and the art work was executed

by Wilhelm Tischbein. He arrived as a youthful painter

in Naples in the spring of 1787 in the company of Johann Wolfgang Goethe,

who was on the southern leg of his Italian

journey.

Tischbein did not travel further, as planned, but

remained in Naples, where he was appointed director of the Neapolitan

Academy of Fine Arts. Tischbein was an ideal collaborator

for Hamilton, since he shared an enthusiasm for the project in hand without overcomplicating the processes. Hamilton’s aims in

publishing his second vase collection remained the same as those that had motivated publication of the first collection. On the one hand, there was a desire to provide models of taste for contemporary

artists and manufacturers and, on the other, he

wanted to furnish antiquaries with a set of images illustrating ancient life, religion, and myth. D’Hancarville had confused matters and overwritten the text of the first publication in his ambition to create a new kind of art history based

on his claims to have discovered the prehistory

of human culture in ancient symbolism. Hamilton

controlled

he

intellectual scope of the second publication himself by writing

the introduction, and while ltalinsky composed the commentaries, Tischbein

and his students reproduced the vase paintings in simple black-and-white outline. This technique contrasted

with the complex color and chiaroscuro of images that d ‘Hancarville had commissioned for the first collection. At first Tischbein’s best pupils at the academy were employed to trace the subjects using oiled paper. This proved

too slow, so a skilled

engraver was hired to draw the vase paintings directly onto a copper engraving plate. The first volume

of an eventual four appeared

in 1793; the fourth volume did not appear until

after Hamilton’s death in 1803, by

which time Tischbein

had even prepared

plates for a fifth volume.

The

actual dates of publication

for Hamilton’s second vase collection do not agree with the dates given on the title pages and

are

generally later than has been supposed. Nevertheless,

the plates circulated separately in advance of the volumes themselves, and Tischbein’s letters to the Duchess Amalia in Weimar

enclosed advance prints. John Flaxman in Rome seems to have been influenced by the sight of such images

when in 1792 he

was working on his outline illustrations for an engraved

set of scenes from the Iliad and the Odyssey. Thomas Hope acquired

the original drawings for these engravings and

also commissioned a set of illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy in the same outline technique that would become Hope’s preferred drawing method, both in the records he made of his travels and in his published works. A Platonic aesthetic of the Enlightenment appreciation of ancient art found virtue in seeing the forms of architecture and sculpture reduced to the simple and chaste outlines

of ancient vase painting. Thomas Hope echoed

a familiar neoclassical principle that moral worth could be found in pictorial

understatement, when in

1805 he wrote to the respected Birmingham manufacturer Matthew Boulton: “Beauty consists not in ornament, it consists in outline- where this is elegant and well understood the simplest object will be pleasing: without a good outline, the richest and most decorated will only appear tawdry.”

Apart from the beauty of their line, Greek vases would also

provide Hope with an encyclopedia of subjects of Greek myth and daily life on which he could draw in devising

his own designs for furniture and costume. Not only did Hope base his designs upon vases, but the British school of history painting, from which Hope himself commissioned a number of works, also took inspiration from

them. From Richard Westall, for example, in 1804 Hope ordered two historical paintings, one

of which, The Expiation of Orestes at

the Shrine of Delphos makes direct reference to the subject of a Paestan bell-krater that Hope is said to have acquired from a

M. de Paroi in Naples, no doubt when he was there in 1802-3. From the dramatis

personae of the vase

painting, Westall selected Orestes kneeling at the Delphic tripod and the naked and beautiful Apollo fending off a Fury. Apollo was posed not as the figure in the vase painting

but in the manner of the Apollo Belvedere. Similarly, spear-carrying Athena in Westall’s painting strongly resembles the Hope Athena.

Hamilton’s attempts to sell his second

vase collection failed,

and in 1798 he was forced to ship it to England, lest his vases should fall into the hands of the French,

who were in Rome and on the brink of marching

on Naples. HMS Colossus was hardly seaworthy, and her voyage out of the Bay of

Naples in late November was to be her last. Moored off the Scilly

Isles in an attempt to ride out a storm, the

ship drifted and foundered on a reef and broke up, spilling

her precious cargo of Sir William’s

vases into the water. The news was shattering to Hamilton, who had been forced to leave Naples

and to exchange his comfortable

home for the cold and gloom of the Bourbon palace at Palermo on

Sicily. At first he clung to the hope that the vases might be salvaged, but in fact very few of them were ever recovered

by the

islanders, and when Roland Morris relocated the wreck and led an expedition in the 1970s to dive for the cargo, all that were found were

many weathered sherds. Now in the British Museum,

some of these fragments have been matched

to the plates in Tischbein’s publication and are themselves published in an exemplary volume, the product of years of painstaking work.

By

November 1800, Hamilton and Emma, now

his second wife, were back in England, where they found a pleasant surprise

awaiting them. The intention had been to load all the best figured vases aboard Colossus,

but the consignment got muddled and many of them had been left off the ship and were dispatched safely to England aboard another vessel. Hamilton spent the winter

of 1801 preparing his vases, along with his pictures and sculpture, for sale at Christie’s. The vase auction never took place,

for Thomas Hope stepped in at the eleventh hour and bought the collection wholesale.

Hamilton had hoped to realize £5,000 but settled for £4,000 and

the satisfaction that the collection would, as he originally

intended, be kept together.

Exactly how many vases Hamilton had sold to Hope is unclear.

In 1796 Hamilton owned about a thousand of them and, according

to his statement that he lost about one third on the Colossus, it is estimated that about seven hundred remained. By 1806, however, we are told that Hope possessed more than fifteen hundred vases,

the result of further purchases as well as disposals. For example, he is said to have sold vases in 1805 and also to have given others to a servant, who sold them to Henry Tresham, who would in turn sell his

vases to Samuel Rogers. Still others went to Frederick Howard,

5th Earl of Carlisle. This shifting of collections from one to another collector is nicely described by

Richard Payne Knight, who wrote a letter dated June 13, 1812, to Lord Aberdeen: “We collectors who have been preying upon each other’s spoils lately

like cray· fish in a pond, which immediately begin sucking

the shell of a deceased brother. Chinnery’s vases went chiefly to Hope, Sir Harry

Englefield, Rogers and

myself.” The

Napoleonic Wars had killed off the Grand Tour

trade, but at home in England there flourished a market in auctions that recycled earlier collections.

The

vases of William Chinnery, brother of the painter George, were sold at Christie ‘s, on June 3 and 4,

1812. The star of the sale was lot 89, an amphora with a battle

between Greeks and Trojans on

one side and a wedding

scene on the other. Now in the Los Angeles County Museum, the amphora was knocked down at the sale for £180 12s to “Henry” Hope, at least according to the annotation

in a

copy of the sale catalogue, and I take this to mean the brother,

Henry Philip, rather than the cousin Henry.

Whether Henry

Philip was buying for himself or for Thomas is not clear, but as we have seen with sculpture, it

may be that a purchase of vases by Henry Philip invariably ended up with Thomas. The origin

of this vase in the Chinnery collection, although

remarked upon at the time, has been forgotten by modern

scholars. In his catalogue

of the Hope vases, Tillyard repeated the false history given it by Millin and reported it

as coming

to Hope via the collection of the bibliomaniac James Edwards. The latter certainly had a large and impressive South Italian vase, a volute-krater for which Edwards is said to have paid 1,000 guineas, but this is not to be confused with the Chinnery amphora now in Los Angeles.

Other vases in the Hope collection were purchased at the sale

of

John Campbell, 1st Baron Cawdor, and that of Sir John Coghill, sold at Christie’s on

June r8 and r9, r8r9. The Coghill

vases were catalogued by Hope’s fellow Dutchman James

Millingen. The most expensive item at the Coghill

sale, at £367 10s,

was a fine Athenian kalyx-krater showing the rape of the daughters of Leucippus

by the Dioscuri in

their chariots. At the Deepdene sale of 1917, it was sold to C. S. Gulbenkian and is now in Portugal. The Cawdor vases were auctioned by Skinner and Dyke on June 5 and 6, 1800, at

which the star piece was the socalled

Cawdor Vase. This large South-Italian volute-krater went not to Hope but to Soane and now graces the courtyard window

of the dining room in Sir John Soane’s Museum. Soane paid £685s, a considerable bargain,

and far less than Edwards paid for his magnificent vase of the same shape. Curiously, the Cawdor Vase,

like the Chinnery amphora, has also been confused with Edwards’s 1,000-guinea vase. At last we can now disentangle the separate

history of these three magnificent but quite distinct vases:

the Chinnery amphora, now in Los Angeles;

the Edwards krater, now in New York; and the Cawdor Vase, now at the Soane Museum.

Hope arranged his vases at Duchess Street

on the east side of the courtyard

in four rooms and illustrated them in Household Furniture. To

judge from these illustrations, the decoration of the rooms was

relatively plain, but as always at

Duchess Street, it was made to reflect

the supposed symbolic meaning of the contents. Hope

had inherited from Hamilton’s generation the notion that, because they were found in tombs vases were sacred and chiefly designed for

the dead and that the scenes upon them

had mainly to do with

reincarnation rites connected to the worship

of Dionysos (Bacchus) as a god of fertility. In Hope’s

own words: “vases relate chiefly

to the Bacchanalian

rites … connected with the representations of mystic death and regeneration.” Hence, he explains, the arrangement of vases in his own first Vase Room featured shelves

divided by supports

terminating in a head of bearded Bacchus. Above these were arched recesses, intended to simulate the niches

of ancient columbaria in the catacombs

of Rome.

Hope would have known that these niches

were, anachronistically, Roman and is likely to have acquired the idea for them from Giuseppe

Bracci’s design for an imagined

tomb

of Winckelmann’s featured in d ‘Hancarville’s book of Hamilton’s vases. This was itself probably inspired by the Tomb of Freedmen

of Livia engraved

in F. Bianchini’s Camera ed inscrizioni sepulcrali dei liberti, servi ed ufficiali della Casa di Augusto (Rome, 1727),

which had been reproduced in the 1750s

by Piranesi.

As in Soane’s later use of the

same motif for vases displayed

in his dining room,

the columbarium niche at Duchess

Street was not intended to be an archaeologically correct setting but simply an atmospheric

reference to ancient sepulchres.

We

feel that atmosphere

more now at Sir John Soane’s Museum

than we do in the rather stringent

record that Hope gives

us of his vase rooms in Household Furniture. For another

impression, there is the self-portrait

drawn in 1813 of Adam Buck and his family. It

so brilliantly captures the essence of Hope’s

Regency taste for vases that it was once thought to be a portrait

of Hope himself. In

a friezelike composition, Buck introduces himself and his family as

an idealized group accompanied by the terminal bust of a deceased child. Further reference

to “mystic death and regeneration,” to use Hope’s own

phrase from Household Furniture, can

be found in the carefully selected

subjects of the vases that occupy the columbaria

and in the relief on the wall showing a maenad and satyr dancing

with the infant Dionysos cradled

in a winnowing basket. The drawing owes much to Hope and much also to Buck’s own knowledge of other contemporary London vase collections, many of which he was recording at the time in a set of outline drawings that he hoped to publish

as a book to rival

Tischbein’s publication of Hamilton’s collection. This project

floundered, and the original

drawings passed upon Buck’s death in 1833 into the library of Thomas Hope’s son

Adrian John Hope and are now

in Trinity College Library, Dublin. Apart from its debt to a thorough knowledge of Greek vases and to the neoclassical revival

of supposed pagan beliefs, it is interesting to note that the seated woman and child in Buck’s

family portrait are composed in direct quotation of Nicolas Poussin’s Holy Family! This painting, which Buck probably

saw in an engraving, doubtless also appealed

to him because of its neo-antique furniture, including a tripod

stand.

The

concentrated, storelike display of Hope’s

vases on bracketed shelves reinforced

the museum character

of his vase rooms. Both

the sculptures and the painted vases relied on Thomas Hope’s genius for presenting them as decorative and, at the same

time, “meaningful” adjuncts

to his distinctive interiors. Indeed, to contemporary visitors the entire arrangement of the first floor at Duchess Street seemed more like a museum

than a house.

Some will have had in mind the newly laid-out Louvre, which had been

witnessed by many British visitors in 1802-3, during the peace of the Treaty

of Amiens. As we have seen, Hope was himself in Paris in 1803 and must have visited

the Louvre before returning to England to open the house in Duchess Street

to the public. Others, in comparing Hope’s house with a

museum, must have had the British Museum in mind, then arranged

in the rooms of Montagu House.

No visual records

survive of what these rooms looked like, but they cannot have been as Greek as those at

Duchess Street. Even George Saunders’s

add-on Townley Gallery, completed in 1808 and designed to accommodate the British Museum’s newly acquired Egyptian and Townley marbles,

was more Palladian than it was Greek. The

British Museum acquired its Greek temple

architecture only when Robert Smirke began to rebuild it from 1823 onward, and it is tempting to see in

his designs a direct influence from Hope. In Smirke’s

grand saloons, there are many echoes

to be found of Hope’s Sculpture and Picture Galleries: the coffered ceilings, top-lit by raised lanterns,

the elongated Doric columns with their shallow echinus, the cornice over doorways on scroll brackets.

All these adaptations of Greek temple architecture for a neoclassical interior were to be adopted by Smirke.

If

Hope’s architectural vision for a temple of the Muses has an

afterlife in the British Museum,

then so too does his museology.

At Duchess Street with its ancient Egyptian, Chinese, Moorish,

Indian, Greek, and Roman collections and symbolic decorations, there was to be found, as in the British Museum then and now, a universal history of mankind.

Visitors could dine at the shrine of an Egyptian mummy, breathe the incense

of the Orient burned in

silver censers mounted on the walls of the Indian Room, observe the lives of the ancients painted

on the body of a Greek vase, or glimpse the exotic present

in a mosque painted

in Hindustan. Hope plays with the boundary

between ancient and modern, real life

and fantasy, sacred and secular.

His was an eventful museum of themed

interiors and evening entertainments, a son et lumière

experience worthy

of Andre Malraux’s Musée Imaginaire, where

world culture stands in place of religion, where no faith is preached but all faiths may be represented.

The

Hope vases remained

at Duchess Street

until they were removed to the Deepdene by Henry Thomas in 1849, pending the demolition of 1851. The sale of a few apparently unwanted vases and other objects is reported in the same year. The

collection was displayed in a

room adjoining the library, which became

known as the Etruscan Room, and part of a complex probably added by Thomas Hope around

1826-31. There in 1912 the vases

were seen and catalogued

by Tillyard for the monograph

he published on them after

their sale and dispersal.

The

sculpture, as we have seen, fared differently from the vases, but even Henry Thomas’s

arrangement of it was to be dismantled when between 1893 and

1909

Lilian, Duchess of Marlborough, took up residence

in the house on a lease. She is said to have disliked the classical art in the Deepdene,

and though previous occupants

had welcomed visitors

to view the collections, the duchess wanted none of it. When in 1917 the

contents were being prepared for auction, the classical sculptures were not even found in

the house but had

been consigned to an ice house

on

the grounds

and to a warren of sand caves. Their excavation from the Surrey sands served only to scatter

them to the winds. Unlike the vases, no

complete pre-sale, illustrated catalogue had been compiled of the sculpture,

and before Geoffrey

Waywell’s book appeared in 1986, it is fair to say that Thomas

Hope’s classical

sculptures had been largely forgotten.

How

now should we evaluate the merits of Hope’s collection?

Viewing his antiquities as a whole, we see nothing

particularly remarkable about them; they are very much a collection of their time.

Hope had none of the pioneering spirit

of Hamilton in respect to his vases, or of Payne Knight and his bronzes

or, notoriously, of Elgin and his Greek sculptures. It is true that Hope had rather more fine Athenian black- and red-figured

vases than Hamilton did, and among them there are some remarkable pieces. Nevertheless, this is only to be expected

in a second-generation collector building

upon the advances

made by Hamilton and his contemporaries in

the understanding of ancient vase painting. Even then Hope adhered, as we have seen, to the mystical

and funereal interpretation of the purpose of ancient

painted vases, which was already

rather old fashioned in his day. In 1822 his

fellow countryman James Millingen condemned this idea of vase painting as a vain

folly and complained that

it had greatly retarded proper understanding. With a remarkably

modernsounding voice he wrote: “The vases of which the origin is supposed to be so mysterious are no others than the common pottery intended for the various

purposes of life and for ornament, like

the China and the Staffordshire ware of the present day.”

In

sculpture too there is nothing

exceptional about Hope’s collection. The mix of Roman portraits, representations

of gods and heroes,

mythical and real beasts, and decorative objects

is what we have come to expect of restored

marbles purchased on the Grand Tour market of Italy. Typically,

there were few or no

sculptures that dated from before the Roman era. Hope’s collection did have its share of works carved in the self-conscious archaizing style of Roman sculpture

evoking Greek originals, which became fashionable with collectors of the later eighteenth

century. Here too, however,

Hope was following an established trend rather than setting a new one. Like other British collectors, including

Henry Blundell of Ince, Hope took his lead from Winckelmann’s pioneering History of Ancient Art of

1764 and the archaistic sculpture Winckelmann found at Rome in the collection of his employer, Cardinal

Alessandro Albani.

Such an assessment of the limitations of Hope’s collecting is

not intended to diminish his achievement. Rather, it enables us to acknowledge that which was truly exceptional about

the man and his collection. Unsurpassed among British collectors of antiquity

was Hope’s sophistication

and poetic sense of style in creating

picturesque settings for his works of art. Never before and never again, with the possible

exception of Sir John Soane’s Museum,

would England see such rooms as those at Duchess Street and the Deepdene, where nature, art, and morality were brought together and combined with

“the ubiquitous presence of death.”

© Bard Graduate Center, Ian Jenkins.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (I968): 93-1, 24; David Watkin, “Thomas Hope ‘s House in Duchess Street,” Apollo (March 2004): 3 1-39.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 110-13.

Household Furniture (18o7): pl. VII.

Ibid., 25.

Geoffrey B. Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures: Ancient Sculptures in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, I986): 100, cat. no. 64.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 113-14; Fani-Maria Tsigakou, Thomas Hope (1769-1831), Pictures from 18th Century Greece (Athens: Melissa, I985): 185), cat. no. 83.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (I 968): 159-61.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (I 986): 54-55.

Tim Knox, “The King’s Library and its architectural genesis,” in Kim Sloan and Andrew Burnett, eds., Enlightenment, Discovering the World in the Eighteenth Century (London: British Museum Press, 2003): 54-57; Thorsten Opper, “Ancient glory and modern learning: the sculpture-decorated library,” in Sloan and Burnett, Enlightenment (2003): 62-65.

Ruth Guilding, “Robert Adam and Charles Townley, the development of the top-lit sculpture gallery,” Apollo I43 (I996): 27-32.

Brian Cook, “The Townley Marbles in Westminster and Bloomsbury,” Collectors and Collections, British Museum Yearbook 2 (1977): 34 -78; Brian Cook, The Townley Marbles (London: British Museum Press, 1985); Ian Jenkins, “Charles Townley’s collection,” in Andrew Wilton and Ilaria Bignamini, Grand Tour, The Lure of Italy in the Eighteenth Century (London: Tate Britain, 1996): 257-62.

Jenkins, “Charles Townley’s collection” (1996): 262-69.

Cited in Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 48- 49.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 227-28.

P. Clayden, The Early Life of Samuel Rogers (London, 1887): 448-49; Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 229.

Thomas Hope, Anastasius, or the Memoirs of a Modern Greek, written at the close of the 18th century, 3 vols. (London, 1819); Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 5-7.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (I968): 232.

Ibid., 42.

National Portrait Gallery, London, inv. no. 4574.

Arthur Hamilton Smith, “Lord Elgin and His Collection,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 36 (1916): 163-370; William St. Clair, Lord Elgin and the Marbles (3rd edition, Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks, 1998): 1-34; Dyfri Williams, “Of publick utility and publick property,” in Athena Tsingarida with Donna Kurtz, eds., Appropriating Antiquity, Collections et Collectionneurs d’antiques en Belgique et en Grande-Bretagne au XIX Siecle (Brussels: Editions Le Livre Timperman, 2002): 103-64.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 154.

Ibid., 83.

Tsigakou, Pictures (1985); Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 65.

Tsigakou, Pictures (1985): 97, cat. no. 29; see also 95, cat. no. 28.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 40.

Seymour Howard, “An antiquarian handlist and the beginnings of the Pio Clementino,” Antiquity Restored, Essays on the Afterlife of the Antique (Vienna: Irsa, 1990): 142-53.

Hugh Honour, “Vincenzo Pacetti,” The Connoisseur (November 1960): 174-81; Nancy Ramage, “Restorer and collector, notes on eighteenth-century recreations of Roman statues,” in Elaine Gazda, ed., The Ancient Art of Emulation, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, supp. vol. I (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002): 68-71, with bibliography at n. 26.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 69-71, cat. no. 3.

Ibid., 72-73, cat. no. 6; now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Ibid., 74-75, cat. no. 9.

Howard, ‘“Pio Clementino” (1990): 151.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 21-22, cat. no. 5); now in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, Liverpool.

Ibid., 73-74, cat. no. 8.

Ibid., 76, cat. no. 10.

Ibid., 90, cat. nos. 36, 37; now in a British private collection.

Jenkins and Bignamini, entry for cat. nos. 204-206, in Wilton and Bignamini, Grand Tour (2002): 250-51.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 93-94, cat. no. 51; now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Ibid., 94-95, cat. nos. 53, 54.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 41.

Ibid., 67-69, cat. nos. 1, 2; both are now in Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Jonathan Scott, The Pleasure of Antiquity, British Collectors of Greece and Rome (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003): 276.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 9, 99; the Hygeia went to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1950 from the Hearst estate.

I am grateful to Michael Stanley for rescuing me from error here.

C. W. Eliot, “Lord Byron and the monastery at Delphi,” American Journal of Archaeology 71 (1967): 290, fig. 4.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 42.

Ibid., 42, 88, cat. no. 31.

Ibid., 100, cat. no. 66.

Ian Jenkins and Kim Sloan, Vases and Volcanoes, Sir William Hamilton and His Collection (London: British Museum Press, 1996): 229, cat. nos. 132, 133; for others, see Carlos Picon, “Big Feet,” Archäologischer Anzeiger (1983): 95-106.

Ian Jenkins, “Seeking the bubble reputation,” Journal of the History of Collections 9 (1997): 197-99.

Ibid., 197, item I; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 85-86, cat. no. 27.

Jenkins, “Bubble reputation” (1997): 97, item 2; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (I986): 8), cat. no. 26.

Jenkins, “Bubble reputation” (1997): 198, item 3; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 86-87, cat. no. 29.

Jenkins, “Bubble reputation” (1997): 198, item 4; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 41, n. 34; Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian: Uma doacao ao Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, no 25 aniversario do Museu de Arte Gulbenkian (Lisbon, 1994): 34-35, no. 10; now in the collection of the National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon.

Jenkins, “Bubble reputation” (1997): 198, item 5; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 97-98, cat. no. 58; See Philip Hewat-Jaboor, “Fonthill House: One of the Most Princely Edifices in the Kingdom,” in Derek Ostergard, ed., William Beckford, 1760-1844: An Eye for the Magnificent, exh. cat., Bard Graduate Center, New York (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001): 54, n. 38.

Jenkins, “Bubble reputation” (1997): I98, item 6; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 91, cat. no. 41.

Jenkins, “Bubble reputation” (1997): 199, item 7; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 106, cat. no. 85, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

John Thackray, “The Modern Pliny: Hamilton and Vesuvius,” in Jenkins and Sloan, Vases and Volcanoes (1996): 67, fig. 31; Jenkins, “Bubble reputation” (1997): 199, item 8; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 100, cat. no. 67.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (I986): 76, cat. no. II; for the new discoveries, see Ian Jenkins, “Neue Dokumente zur Entdeckung und Restaurierung der Venus Hope und anderer Venus Statuen,” in Max Kunze and Stephanie-Gerrit Bruer, eds., Wiedererstandene Antike, Ergänzungen antiker Kunstwerke seit der Renaissance (Munich: Biering and Brinkmann, 2003): 181-92.

Charles Molloy Westmacott, British Galleries of Painting and Sculpture (London: Sherwood, 1824): 221; now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 9.

Ibid., 20.

Ibid., 21.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 101-4; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 42-49.

Ian Jenkins, Archaeologists and Aesthetes in the Sculpture Galleries of the British Museum (London: British Museum Press, 1992): 41-44.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 45, fig. 3.

Ibid., 50-56.

Ibid., 57-61.

Ibid., 62-66.

R. M. Cook, Greek Painted Pottery (3rd edition, London: Methuen, 1997): 275-311; Dietrich von Bothmer, “Greek vase-painting, two hundred years of connoisseurship,” Papers on the Amasis Painter and his World (Malibu: Getty Trust, 1987): 184-204; Vinnie Nørskov, Greek Vases in New Contexts (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2002): 27-34.

Jenkins and Sloan, Vases and Volcanoes (1996): passim.

Claire Lyons, “The Museo Mastrilli and the culture of collecting in Naples, 1700-1715,” Journal of the History of Collections 4 (1992): 1-26.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (Dresden, 1764): 123; Ian Jenkins, “D’Hancarville’s ‘Exhibition’ of Hamilton’s Vases,” in Jenkins and Sloan, Vases and Volcanoes (1996): 153.

A. Morrison, A Catalogue of the Collection of Autograph Letters and Historical Documents formed between 1865 and 1882 by A.Morrison: The Hamilton and Nelson Papers, vol. I (1893): 180.

Ian Jenkins, “Contemporary Minds: Sir William Hamilton’s Affair with Antiquity,” in Jenkins and Sloan, Vases and Volcanoes (1996): 52-55; Valerie Smallwood and Susan Woodford, Fragments from Sir William Hamilton’s Second Collection of Vases Recovered from the Wreck of HMS Colossus, Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum, Great Britain, Fascicule 20, The British Museum Fascicule 10 (London: British Museum Press, 2002): 11-12.

Jenkins, “Contemporary Minds” (1996): 58.

Frances Haskell, “The Baron d ‘Hancarville, an adventurer and art historian in eighteenth-century Europe,” in E. Cheney and N. Ritchie, eds., Oxford, China, and Italy: Writings in Honour of Sir Harold Acton (London: Thames & Hudson, 1984): 177—91; reprinted in Haskell, Past and Present in Art and Taste, Selected Essays (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1987): 30-45; Michael Vickers, “Value and simplicity: a historical case,” in Michael Vickers and David Gill, Artful Crafts: Ancient Greek Silverware and Pottery (Oxford: Clarendon Press, I994): 1-32, a revised version of “Value and Simplicity: Eighteenth-century taste and the study of Greek vases,” Past and Present I 16 (1987): 98-137; Jenkins, “Contemporary Minds” (1996): 45-51; Ian Jenkins, “Talking Stones: Hamilton’s Collection of Carved Stones,” in Jenkins and Sloan, Vases and Volcanoes (1996): 93-101; Jenkins, “D’Hancarville’s ‘Exhibition”’ (1996): 149-55.

Jenkins, “Contemporary Minds” (1996): 55-57; Smallwood and Woodford, Colossus (2002): 13-16.

F. von Alten, Aus Tischbein’s Leben und Briefwechsel (Leipzig, 1872): 50-54 (letters dated 11 December 1790 and 19 March 1791).

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 35; David Irwin, John Flaxman 1755-1826, Sculptor, Illustrator, Designer (London: Studio Vista, 1979): 68, 81-83; David Bindman, “Studies for the Outline Engravings, Rome, 1792-93,” in John Flaxman, ed. David Bindman (London: Thames & Hudson, 1979): 86.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 30-33.

Ibid., 35-36, 51-52.

George Cumberland, Thoughts on Outline, Sculpture, and the system that guided the ancient artists in composing their figures and groups, etc. (London, 1796); Vickers, “Value and Simplicity” (1987): 129 ff.; Hans-Ulrich Cain, ed., Faszination der Linie, Griechische Zeichenkunst auf dem Weg von Neapel nach Europa, exh. cat., Leipzig, Antikenmuseum der Universität (Leipzig: Leipzig University, 2004).

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 198 (Hope to Boulton, 14 September 1805, Birmingham, Boulton Papers, ff. 2-4).

Ibid., 43.

E.M.W. Tillyard, The Hope Vases (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1923): 137, cat. no. 267.

Smallwood and Woodford, Colossus (2002): 16-17.

Ibid., passim; now in the collection of the British Museum, London.

Jenkins, “Contemporary Minds” (1996): 58-59.

Morrison, Hamilton and Nelson Papers: 552, Hamilton to Greville, 3 April 1801.

A. L. Millin, Monuments antiques inédits ou nouvellement Expliqués, vol. 2 (Paris, 1806): 15, quoted by Tillyard, Hope Vases (1923): 2.

Adolph Michaelis, “Die Privatsammlungen antiker Bildwerke in England, Deepdene,” Archäologische Zeitung 32 (1874): 15-16.

Ian Jenkins, “Adam Buck and Greek Vases,” Burlington Magazine 130 (1988): 454.

R. Liscombe, “Richard Payne Knight, some unpublished correspondence,” Art Bulletin 61 (1979): 606.

Photocopy of annotated copy in the library of the Greek and Roman Department, British Museum, London; it is now in the Los Angeles County Museum.

James Christie, Disquisitions upon the Painted Greek Vases and their Probable Connection with the Shows of the Eleusinian and ocher Mysteries (London, 1825): vi.

Los Angeles, inv. no. A5933; A. L. Millin, Peintures de Vases Antiques vulgairement appelés Etrusques (Paris: M. Dubois Maisonneuve, 1 808): 94, pls. 49, 50; Tillyard, Hope Vases (1923): 149, cat. no. 283; A. D. Trendall, The Red-Figured Vases of Lucania, Campania and Sicily, vol. 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967): 339, no. 799; Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Los Angeles r (1977): pls. 46-47.

Jenkins, “Adam Buck” (1988): 455, figs. 68, 69; 457 s.v. Soane; now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

James Millingen, Peintures antiques de vases grecs de la collection de Sir John Coghill (Rome, 1827).

It is now in the Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon; Lisbon, inv. no. 682; A Catalogue of Painted Greek Vases, Bronzes, Coins, ancient and modern Sculpture etc. The property of Sir John Coghill Bart. deceased and formed by him at a great expense during his residence a few years ago in Italy, which will be sold by auction by Mr Christie, Friday, June 18, 1819 and the following day: 19 June, lot 109: photocopy of annotated copy in the library of the Greek and Roman Department, British Museum, London; Millingen, Coghill (1827): pls. 1-3; Tillyard, Hope Vases (1923): 65-68, cat. no. 116; John Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters (2nd ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963): 1042.1.

Soane Museum, inv. no. 101 L; Cawdor Sale: Catalogue of Antique Marble Statues and Bustoes with Etruscan Vases etc., Skinner and Dyke, London, 5-6 June 1800: second day, lot 64; Soane Journal 4, fol. 27I, 9 June 1800, for confirmation of the price; A. D. Trendall, The Red-Figured Vases of Apulia, vol. 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, I982): 906—7, 931-32, no. 119.

Jenkins, Adam Buck (1988): 454, 457 s.v. Soane.

Watkin, “Thomas Hope’s House” (2004): 35, fig. 14.

Household Furniture (1807): 23.

Ibid., 34.

Thackray, “The Modern Pliny” (1996): 148, cat. no. 31.

Jenkins, “Adam Buck” (I988): passim.

Ian Jenkins, Adam Buck’s Greek Vases, British Museum Occasional Paper 75 (London: British Museum Press, 1989); now in Trinity College Library, Dublin.

Ian Jenkins, “Athens Rising near the Pole, London, Athens and the Idea of Freedom,” in Celina Fox, ed., London World City 1800-1840 (London: Verlag Aurel Bongers Recklinghausen, 1992): 147. The painting is now in the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 104.

Jenkins, Archaeologists and Aesthetes (1992): 102-10.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 121, 240-42.

Adolph Michaelis, “Museographisches-Vasen des Hrn. Hope,” Archäologischer Anzeiger 7 (1849): 97-102.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 180-81; Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 60.

Tillyard, Hope Vases (1923): 2.

Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (1986): 63.

James Millingen, Ancient Unedited Monuments, Painted Greek Vases from Collections in Various Countries, Principally in Great Britain (London, 1822): iv-vi. For the changing taste and opinion of the times, see Ian Jenkins, “La vente des vases Durand (Paris 1836) et leur reception en Grande-Bretagne,” in A.-F. Laurens and K. Pomian, L’Anticomanie, La Collection d’Antiquités (Paris: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 1992): 269-78.

Watkin, Thomas Hope (1968): 242.