It has been a long and trying year. The pandemic has made many of us very aware that when we are confined to our homes and missing the company of others, we turn to our belongings and look inward for comfort. Self-care can sometimes be the best therapy, whether that means pampering oneself or taking up new hobbies and intellectual pursuits. For some, this has been an opportunity to devote more time to self- and home-improvement, so it was particularly fitting that the topic of the second Student Research Forum was “Mind, Body, Spirit: Objects of Wellness and Self-Cultivation.” Second-year MA students Weixun Qu, Madison Clyburn, and Natalie De Quarto discussed “Antiquities in Women’s Decorative Patterns in Qing China,” “The Philosophy of Aroma in an Italian Renaissance Incense Burner,” and “Status and Health Through Domestic Horticulture in Nineteenth-Century America,” respectively. Offering a bit of academic solace in the middle of a particularly snowy January when many of us were hitting a pandemic wall, these presentations reminded us that the idea of wellness has a long and varied history.

It’s safe to assume that while we have been housebound, many of us invested in more comfortable clothing, forgoing jeans, heels, and suits for slippers, sweatpants, and cozy sweaters. Qu’s presentation on a Qing dynasty robe illustrated how aristocratic Chinese women made enforced leisure luxurious thousands of years ago. She focused on the burial robe of Princess Rongxian, which was decorated with an intriguing pattern featuring antique vessels, flowers, feathers, and fruit. Qu explained how this robe signified more than just a comfortable lifestyle, as it reflected the belief that one could purify and improve the body and spirit through the study of antiques. Once thought to only be a suitable activity for men, during this period, more aristocratic women began to stimulate their minds and engage in scholarly pursuits. Through displaying this interest on their clothing, they hoped to become more cultivated and live a long life.

Clyburn drew the audience’s attention to the world of Italian scholars in her discussion of an ornate incense burner that would have decorated the intimate space of an Italian Renaissance studiolo, where well-to-do men would study and write. Evoking the familiar and soothing scent of incense, she pointed out that Italians discovered incense through engaging in trade with the Ottoman Empire, and that it was thought not only to purify the air and ward off disease, but also to balance one’s sentiment and strengthen the mind. With a shape inspired by a cathedral candelabra and decorations of hybrid forms from Greek mythology, the incense burner also expressed ideas of spiritual transformation.

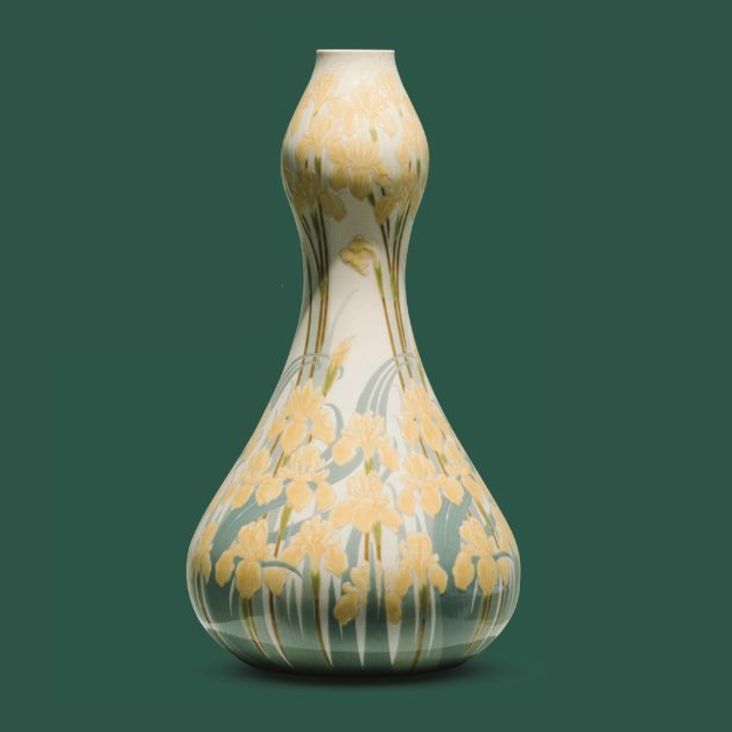

De Quarto’s presentation illustrated that the practice of bringing plants indoors was considered a new way to purify the air within the domestic interiors of nineteenth-century America (especially in cramped city dwellings). Although an obsession with houseplants has been flagged as a millennial trend, it seems we are just following in the footsteps of the Victorians. De Quarto’s interest in researching this subject (as well as her qualifying paper on Wardian cases) was inspired by Freyja Hartzell’s course, “Living Things: Biology, Modernity and Design in the Long Nineteenth Century.” While looking through Victorian gardening manuals, De Quarto found that the ability to keep one’s plants alive was connected to ideas of cleanliness, morality, health, and status. Plant-tending was encouraged as a distraction from vice and a way to educate children on how to be useful members of society. She pointed out that in some ways, “plants cultivated their caretakers.”

All these topics provided much food for thought on how we relate to our belongings in similar and different ways than societies of the past. In reflecting on the current obsession with houseplants, De Quarto observed that on Zoom she sees “a lot of people with plants in their backgrounds. Maybe some just happen to be there, but I’m sure others are strategically placed as décor, or to show off a thriving plant.” The simple acts of slipping into comfortable pants, lighting a stick of incense, or watering a fiddle leaf fig are continuations of historically symbolic practices that still resonate and enhance our sense of well-being.