Recently, Bard Graduate Center allowed a first-year MA student, Mackensie Griffin, to turn the tables, so to speak, and ask the questions of Deborah Krohn, associate professor and chair of academic programs at BGC. This is the first of what we hope will become a series of conversations between faculty members and students or alumni who share research interests.

Mackensie Griffin (MG): Hi Deborah. Your research and teaching areas include early modern European cultural history, the history of the museum, culinary history, and the history of the book. Before coming to Bard Graduate Center, I received a master’s degree in food studies from NYU and became interested in the material culture of dining, so we have some interests in common.

I was excited to see you in the documentary, Ottolenghi and the Cakes of Versailles, which is available to stream on Amazon, Apple TV, Hulu, and others. It covers preparations for an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art inspired by dining at Versailles, curated by Yotam Ottolenghi, the popular Israeli English chef and cookbook author. How did you become involved in this project?

Deborah Krohn (DK): I worked at the Met for a long time in the nineties. I have a lot of friends there who know that I work on food. The person who organizes the Met live events, Limor Tomer, asked around for someone to be an advisor for that project once Ottolenghi was on board, and the curator of the Visitors to Versailles exhibition, Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide, suggested me. So that’s how I got involved. I got an email out of the blue one day, about a year before the event, asking if I would be interested. And of course, I was thrilled and very excited about it!

MG: Have you ever advised on a project like this before?

DK: Years ago, I was asked to advise on a dinner for 150 people that was being given at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in association with the opening of an exhibition about Medici patronage. I consulted with the company that was doing the dinner. They told me some of the things they were thinking of serving, including all these foods that they definitely would not have had in sixteenth-century Florence—potatoes, tomatoes, and coffee—all the new world foods. I just said, “Depending on how authentic you want to be, you can’t serve all these things.” And of course, they’re not going to serve dinner without coffee or tea. People would wonder, why is there no coffee after dinner? There was an interest in some kind of authenticity, but more interest in having a nice dinner in the museum. They had to strike a middle ground. I realized that there’s only so far you can go for a big institutional event if you’re trying to do it authentically. People might be interested in reading about an authentic meal, but they’d rather eat a good one in the end.

MG: Yes, the best marriage is something both authentic and delicious.

DK: Also, what does authentic really mean? Even if you say, I’m going to follow a recipe for roast chicken from the sixteenth-century, the chicken would bear no resemblance to what chicken was like in the past. Even an organic, free-range chicken is going to be different than a chicken from a farm surrounding Florence in 1590. It’s a different animal. Preparing food from old recipe books can be a fascinating experience, but you can’t really convince yourself that it’s totally authentic.

MG: I think the limits of trying to create something from the past in modern times does make for an interesting challenge. And that was what was fun about the Ottolenghi documentary. It was sort of part Great British Bake Off, part 7 Days Out, the Netflix series. You have the chefs working within the constraints of a museum and then the academic side of things. I thought it was great that Ottolenghi referred to you as his “food history guru” in the documentary.

DK: That was gratifying, I must say.

MG: That’s a nice title. And I was curious, since you’re coming from an academic perspective, what was it like working with a chef like Ottolenghi?

DK: I was in Paris nine or ten months before the event, so I went to London for the day to meet him. I took the train and I went to his test kitchen: it’s a little bit outside the center of London, in a kind of a funky, cool neighborhood. And I walked into this kitchen, which was really pretty modest. It wasn’t like a giant, industrial kitchen with hundreds of people. It was a pretty small space with a couple of people cooking and a library of recipe books. Somewhere between a professor’s study and a kitchen, which is sort of the way he is. And he said, “Have you had lunch yet?” And of course, even if I’d just had a five-course meal, I would have said no. He said, “Well why don’t you try this, we’re just testing this recipe.” And he put something on a plate, and you know, he’s completely relaxed.

Anyway, I had sent him a bunch of stuff beforehand because initially I had thought, “Well, okay, I’m a historian of food, I’m going to put together a lot of information about the kinds of food that would have been served at big events at Versailles, because we have recipe books from this period, and we have all kinds of other types of accounts. We know quite a bit about what a meal would have consisted of and what it looked like, and what the ingredients were.” So I put that together from both the primary sources and from the actual recipe books—La Varenne and some other ones, and then also from secondary sources that talked about the whole historical setting.

And then I realized that they were really just not interested in that kind of authenticity. They were more interested in capturing the spirit of what a festive banquet would have been like at Versailles, and I think they decided to do the cakes and desserts because it was too hard to do a whole meal for that number of people. And the sweets were something that you see represented in lots of images of garden festivities at Versailles. I realized he wasn’t going to approach it at all from a perspective of historical accuracy or authenticity, but it was going to be about the aura, the idea of spectacle, using food as a medium for display of wealth and prestige, the way the ingredients were sourced and where they were grown. All of these themes came into the program in a way that showcased these pastry chefs. So in a sense, I was just there to be the straight man and give the history. Then the event was riffing off of all of those themes that I had provided—the pyramids and the shapes, and the partiers and their relationship to the gardens, and the meals that took place in the gardens. It was an interesting process because in a sense they wanted history, but they also wanted to completely throw history out the window.

MG: Right, a lot of the chefs created very modern style pastries just as the pastries served at Versailles were new inventions showcasing new technologies.

DK: Right, and when we think of cake, like a wedding cake or a birthday cake, sixteenth-century cakes weren’t really like that. It was the very beginning of the idea of a big thing that’s sort of like bread in that it rises. They would have had things like choux pastry and butter cream at Versailles, and there were definitely elements of what a modern dessert menu might look like, but they were combined in different ways. Yotam [Ottolenghi] and the Met could have just gone with the whole tradition of French pastry, but instead they asked people from all these countries and traditions to come up with interpretations. And I think it was a much more interesting event for that reason.

MG: I also thought the variety of chefs was really compelling. Especially within the context of the Visitors to Versailles exhibit, which showed how they welcomed people from all over the world. I know one of the chefs, Ghaya Oliviera, who used to work at the restaurant Daniel, and it was really great to hear more about her story of growing up in Tunisia.

DK: She was actually one of the more traditional French chefs in the program, and the thing that she created was more traditional than a lot of the other ones because it was all chocolate. In some ways that was more authentic and in other ways completely not authentic at all, so very interesting.

MG: Yeah, it was very interesting to see everyone’s interpretations of the theme.

DK: So I was involved as an advisor on the project and then a couple of weeks before the event I got an email saying there was a documentary filmmaker who would be filming and is that ok? They did an interview that took place in my apartment with Yotam and the film crew, and then they filmed a bunch of stuff in the days leading up to the event. And then the event happened, and it was wonderful, and then for two years I heard nothing. They had set a date to release the film at the Tribeca Film Festival in April of 2020, and then of course that got canceled by the pandemic, so I didn’t actually see it until it was released to the public in October 2020. I had no idea that they had gotten all of that great footage. It was a big surprise to me when the film came out and my name was there as one of the people in the movie.

MG: That must have been very exciting. Did you enjoy watching it?

DK: It was great. I think the filmmaker did a great job of making it into a story about luxury and excess in the age of Versailles and the parallels with the current situation. That was really very deft and made it into something that is not simply eye candy. There’s almost a kind of moral to it that gave it a little more substance, and I thought that was an incredibly smart way to deal with this pretty frivolous subject and give it more of a contemporary spin to contextualize Versailles for people. It puts it in the context of something that had its moment, but ultimately led to the downfall of the Ancien Régime.

MG: I agree. Do you enjoy cooking or baking at home?

DK: I do. I enjoy cooking for my friends and family, and I tend to stick to recipes that are relatively simple, that don’t require days of preparation. And I spend a lot of time reading through recipe books. Just today, I was thinking about making a soufflé this weekend, because I’ve been reading up on soufflés, and so I looked at Julia Child, and then I looked online and I found a recipe on food52 (a website that I love) that was a very simple Jacques Pepin recipe that was the complete opposite of the Julia Child, and I’ll probably do something that’s in between. I shouldn’t have been doing any of that, I should have just been writing my book, but for me it’s extremely relaxing to read through recipes. I enjoy cooking, but it’s something that’s more of a hobby. I’ve never been interested in any kind of professional work in that world. I think it’s a form of relaxation, and it’s definitely a metaphor for other types of creative work. If I have a big project, if I’m cooking something at the same time, it sort of metaphorically helps the process along. The thing about cooking is that you can choose a recipe and go and buy the ingredients and cook the thing and however it comes out, it’s done. And it’s usually reasonably tasty unless you completely screw up. So it’s the opposite of writing a book or curating an exhibition which takes years. With cooking, there’s an immediate gratification, and it’s sometimes nice to do something that gives you that sense of completion. I think for a lot of people, especially during COVID, cooking has served various therapeutic roles that it didn’t before. I had never baked bread, but that’s something millions of people started doing during the pandemic. If you’re home all the time, you can bake bread, but if you leave the house at eight in the morning and never get back till six or seven, it’s impossible.

MG: Definitely. Having the time is critical for doing complex cooking or baking projects. I guess in the case of bread, it can almost be like having a pet that you tend to, if you’re doing a sourdough starter and all that.

DK: Yeah exactly.

MG: So now I want to talk about your upcoming exhibit, although I know it’s been delayed because of COVID.

DK: Right, it’s supposed to open in February 2023 now.

MG: I see. I know the title is Staging the Table in Europe, 1500–1800, so I was wondering if you could just explain the focus of this exhibit and the kinds of things that will be on display.

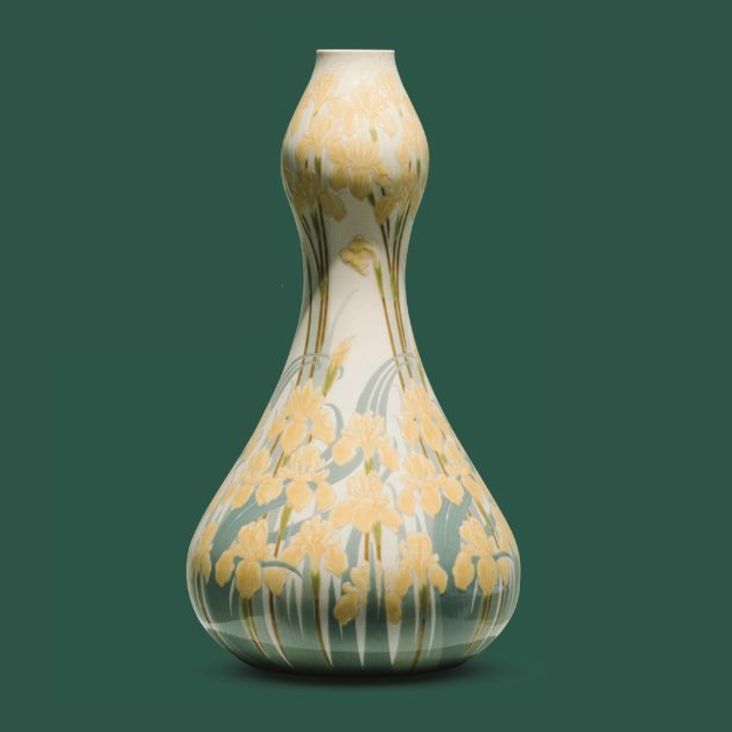

DK: The focus is a group of printed books from 1500 to the middle of the eighteenth century that deal with food presentation and table setting, including the performative carving of meat and fish, and the artful slicing of fruits and folding napkins. Napkin folding was very elaborate in Italy, Germany, and France. And there are these books that give detailed instructions on how to make the folds and how to create elaborate shapes from the folds. It’s related to origami and to mathematics. It’s a very interesting group of ideas that coalesce around the table.

So, the exhibition will focus on the illustrations and these books as well as some carving tools—cutlery that the carvers would have used. Some of it that has survived that is quite elaborate and beautiful. I’m hoping to have loans from museums’ decorative art departments, including the Met, and some napkins. I even have some napkins that were folded by a master folder for an exhibition at the Met ten years ago.

It’s really about the constellation of knowledge that was focused on the realm of the table as a parallel to the Kunstkammer or the Wunderkammer, which was a much more permanent place for elaborate displays, a lot of them made with natural objects, but I found in some of these manuals that the sliced fruits are referred to as wonderful, and there’s some of the same language that you would find describing amazing natural wonders. Nature, in the form of, in this case, fruit, is manipulated by a skilled carver and there is something kind of magical about it.

That’s another theme that reoccurs in the manuals—the idea of sleight of hand and how that’s part of the entertainment factor of it. And then there are a few books from Northern Germany and Scandinavia, from the second half of the eighteenth century, that have magic tricks included along with some of the carving stuff, so that in a way, to me, is a natural development of the idea of performance and entertainment and how that is something that takes place at the table. I’m hoping that by bringing all of these kinds of books together with these illustrations, some of which are pretty fantastic and interesting, that people will get a real sense of this relatively obscure pocket of knowledge from early modern Europe.

MG: It’s interesting because while I was studying food culture at NYU, I did become interested in the material culture surrounding food, as in objects used for cooking and dining, but I never really thought of food itself as material culture because of its ephemeral nature. So, I think it’s really interesting to now consider it in this way.

DK: Well, it’s really clear that for them, it was just another material that could be manipulated and made to perform certain roles on the table that were part of other types of rituals involving poetry and music and theater, and all of this was happening at the same time. And of course, all of that has disappeared, right along with all these other ephemeral arts, although some of the music survived. One of the books I’m most interested in is a German book that translates parts of an Italian carving and folding manual that was first published in Padua in 1629. Later, a lot of it was combined with topical reports of huge banquets that were celebrated in Nuremberg to mark the end of the Thirty Years War in 1649. So in the version of this book that was published in 1652, all of a sudden you find, in addition to some references to older historical banquets that come directly from the Italian sources, these completely topical events that took place that included writing emblematic poetry and a play. And we know that there were composers who wrote special music for these events. So it’s a completely fascinating combination of both long traditions and the very topical—almost like a form of journalism or reportage, and this was happening all over Europe in the seventeenth century. All these official events were being disseminated via print culture in various ways. And as soon as print became cheap enough and literacy became widely dispersed within the culture, reading about these events became an important demonstration of power for European rulers to demonstrate the prestige of their table. All these things are kind of wrapped up together, and I hope, by showing little bits and pieces, a sense of the ubiquity of this culture all over Europe from the late sixteenth century into the early eighteenth century will be demonstrated through objects.

MG: Were the manuals made to be circulated among the elites?

DK: I think initially they were used for educational purposes—the carvers would give them to their students, and the students would make notes in them. But others became like Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, and they were for people to get a sense of what would happen at the tables of the elite. There were many different pirated versions, and they were published all over Europe, so clearly they were not only read by the elite, but they were read by aspiring bourgeois middle-class people who wanted to try to recreate a little bit of that in their own homes or just to read about it in the same way that we read recipes, purely as aspirational. We don’t really know, in most cases, exactly why these books were published, but just the sheer number of publishers who invested the money to publish them tells us it must have been a good business.

MG: Have you tried to follow any of these instructions as part of your research?

DK: I have tried with paper. In some of the treatises they mention that you can practice with paper because it’s easier to manipulate than the starched linen, but I have had very little success. They’re very complex. I think people who are good at origami might be able to do a lot more of it; some of the basic origami folds are exactly the same. And in fact, the traditions of folding all around the world kind of mix and meld, and I think a contemporary origami master would look at these treatises from seventeenth-century Germany and would think, this makes a lot of sense.

I don’t know how practical these books were, because a lot of what was being taught or explained was still being transmitted largely through practical apprenticeships and training. I’m really asking, what was the purpose of these written instructions, and how well did they work. It’s pretty hard to follow them unless you have someone explaining them at the same time. From my perspective, there’s a lot of tacit knowledge that’s left out.

MG: Do you see an evolution of dining trends over the 300 years these manuals cover?

DK: There are changes, but part of what’s interesting to me is what is static. There’s a certain kind of choreography of carving that is really consistent from the first illustrated manual from the 1580s to twentieth century books that show you how to carve your Thanksgiving turkey, for example. So, the sheer continuity of the tradition is something that interests me. Of course, what people are actually serving on the table, what they’re eating, the recipes, there’s definitely an evolution there. But in terms of carving, it’s pretty static I would say, and these traditions are still very much present.

MGe: Thank you, Deborah. I think it’s a fascinating subject, especially for anyone interested in food, and best of luck with the upcoming exhibition!